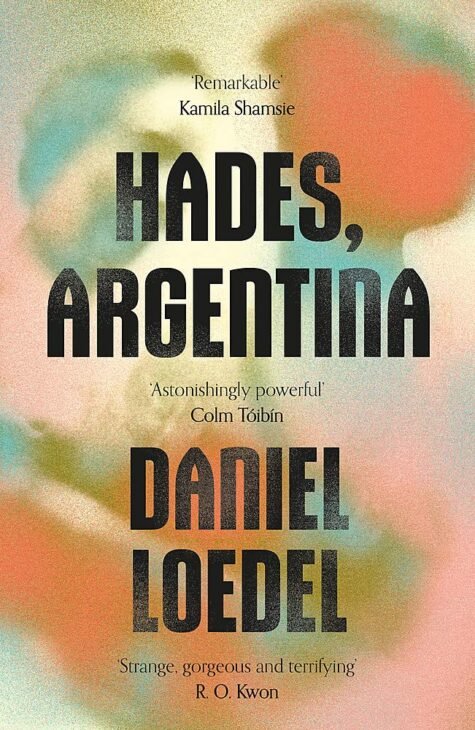

Daniel Loedel, an American book editor, takes readers back to that dark time in the 1970s when Argentina was indeed hell. Both for the innocents living under the country’s dictatorship who were routinely kidnapped, tortured and murdered (the “disappeared”), and for their families who had to carry on without knowing their loved one’s fate.

In 1976, Tomás Orilla was a medical student and spy for the resistance. Facing an almost certain death, he was smuggled out of Argentina by his mentor, the Colonel, an operative for the state.

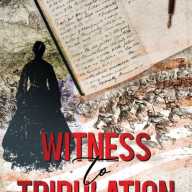

“Hades, Argentina” by

Daniel Loedel

Fiction / Riverhead Books

Fast forward 10 years, and he’s Thomas Shore, a translator in New York City who is haunted by his past. Stuck in a should-I, should-I-not-divorce-my-wife? marriage, Thomas is relieved when he is summoned to Buenos Aires by his mother’s old friend, Pichuca, who is dying. It’s a chance for him to get away and sort things out. But the real reason is Isabel, Pichuca’s daughter, his love of years ago. Still smitten, and guilt-ridden (more about that later), maybe he can see her again.

She has grown very thin, his Isabel. “The skinniness of her limbs,” throws him off. “She seemed so small suddenly.” His spirited, fiery Isabel is dead. Tomás has made love to a ghost.

Confused? So was I. And disoriented, till pages on I discovered I had been caught in Tomás’ haunting dream – self-torture might be a better word – where time and consciousness shift, images blur then clarify.

That’s Loedel’s magic realism pulling readers into, then yanking them out of real time. One minute Tomás is in his hotel room, the next, he’s a medical student in the underbelly of Argentina, where “the sky has the slippery iridescence of fish scales.” Or as the Colonel, himself now a ghost, puts it: “The border, it’s very real. But it’s thin, porous in a way. There are more ways to cross it than you think.”

Both mentor and tormentor, the Colonel takes Tomás “down memory lane,” to a crypt under an old illegal detention center. The locus of Tomás’s private hell from which he craves redemption.

The narrative voice is polished, the drama paced just so. This book does not read like a first novel.

“The train pulled into the station at Constitución, and we got off with the rest of the crowd … The buzz of activity grew as we reached the main hall, then became a throb, the tall, arched ceiling amplifying the sound … military figures and men carrying crosses, haloed women … ‘I don’t recognize those,’ I said to the Colonel, still gaping upward as bustling apparitions brushed by me. ‘I’m sure there will be much you don’t recognize here at first,’ the Colonel said. ‘But don’t worry. This place, it recognizes you.’”

Enamored with Isabel’s spirit, “powerless before her, a toy in her grasp,” Tomás becomes a spy for the Monteneros. He will report what he sees and hears to Isabel, and the names of the people taken. When he finds himself in the torture room using a defibrillator to resuscitate a hostage for more torture, he questions himself. Whom is he helping? Whom is he saving? “And yet. And yet and yet and yet,” he thinks. Can he abandon the work? Not when Isabel tells him it’s not about him, it’s about “war.” But it wears on him, and one day he plans the escape of two prisoners. He is found out.

Now the gag is in his mouth. The hood over his head. “The unwrapping of a cord, the methodical adjustment of the rheostat … 14,000 volts was what they settled on. The low, droning thrum of the picana gliding ever nearer…”

The torture scenes were a challenge for me to read but necessary to review the book, as I imagine it was a challenge for Loedel to document the regime that dropped live victims from airborne planes “into the depths of the Río de la Plata. One at a time they fell … like fat drops of rain.”

Tomás survives his physical torture, but he is hollowed out from guilt and regret. Could he have done more to save Isabel? What would the more have been? Sacrifice his own life then? She would have been killed anyway. Maybe she was dead already? he reasoned – still reasons. Tomás asks unanswerable questions. The questions we all ask when we want to go back and change the unchangeable.

Loedel’s novel is a personal one. His half-sister Isabel Maiztegui, a Montonera (resistance fighter), was murdered by the Argentine dictatorship in 1978 when she was 22. It wasn’t until four decades later that her remains were delivered to him for interment. He notes that the book, dedicated to Isabel, “could not have been written without her sacrifice.”