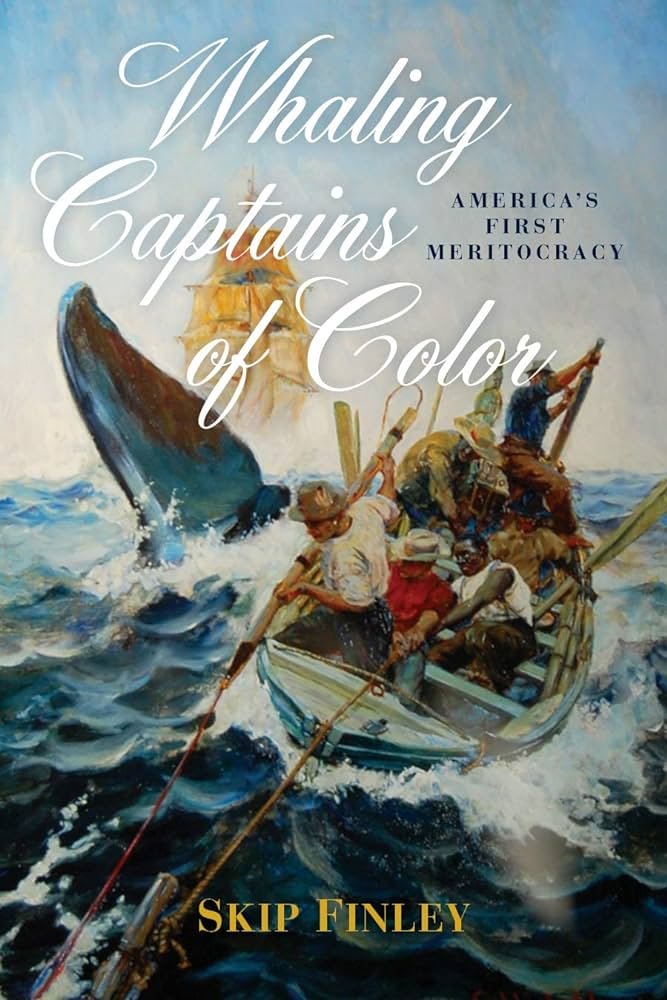

Whaling Captains of Color: America’s First Meritocracy

by Skip Finley

Non Fiction

Naval Institute Press

Award winning journalist and former broadcast executive, Skip Finley became interested in black whalers while researching for an article on the “Charles W. Morgan,” the last wooden whaling ship (circa 1840’s), and discovered the captain was Black. Not only was that captain a man of color, Finley found out, but there had been dozens of Black captains commandeering whaling ships around the world before, during and after that time.

If, like this reviewer, your knowledge of the great cetaceans (ci-tay-chins) has been limited to Ahab’s run-in with Moby Dick, you have climbed aboard the right boat.

Used first for candles to light homes, then for street lighting, whale oil greased the wheels of the Industrial Revolution, and from the 1600s to the 1800s, whale oil meant big business for America. A valuable commodity and one of our largest industries, whaling was also a brutal and dangerous way to make a living.

In a chapter headed “How Hard Was Whaling,” the author tells of sleeping quarters close and filthy, disease at every turn. Punishment for even minor infractions was fast and severe.

A 50-ton harpooned whale was not a happy camper. It’s huge thrashing tail could easily capsize an open whaling boat, throwing the whalers into to the sea, a toothsome snack for sharks perusing the waters for dinner. If the men survived all that, there was hauling the behemoth back to the ship, the carcass carved up for the blubber. Working on a slippery deck with razor sharp tools, cost many a whaler a digit or two.

“There were a million ways to die on a whaling ship,” said Finley.

With the men going without women for years on end – whaling ships were out that long – tempers ran high. As did mutiny. Finley’s extensive research shows that out of 750 ships that left New Bedford through the years, hundreds of munities were recorded.

Given the dangers and hardships, who would want to be a whaler?

Blacks, and the “dregs of early American society: former or soon-to-be-prisoners, runaways, the disinherited… literally the unwanted and uncared for,” would. Fredrick Douglass was the exception. Born into slavery, the great American social reformer and statesman worked as a caulker as a young man, sealing the joints on wooden ships.

When men of color had little chance of any work, whaling offered not only a livelihood, but blacks could advance and become leaders in their profession based on their abilities rather than skin color.

Among the lives of the 50 Black seamen who earned their place as captains of America’s great whaling ships, Paul Cuffy (1759-1817), Paul Cuffy stands out. Not only did he captain his ship, he owned it, and employed an all-black crew. Folks know about Cuffy through his own writings and books written about him.

Many Native Americans also sought out whaling; those of the Shinnecock Nation were known to be exemplary sailors. Michael (Micah) Quaben Wainer (1748-1815), was a lesser-known Indigenous captain of color. His third wife, Mary Slocum Cuffe, was Paul Cuffe’s sister. When the two families went into business in the early 1790s, they caught six whales in their first year of partnership, “two of which Cuffe personally harpooned himself.” Finley’s meticulous research notes the kinds of whales they caught.

In an engaging narrative, the author uses logs, charts, articles and firsthand accounts as he provides an in-depth study of the whaling industry, including the building of the ships and those who built them, played out against the social and racial climate of its time.

Finley’s vision has earned him the 2020 Award Winner for Non-Fiction by the Afro American Historical Genealogical Society. In 2021 he was given the Author of The Year by the United States Naval Institute Press, for “Whaling Captains of Color—America’s First Meritocracy.”

All told, it’s a whale of a book.