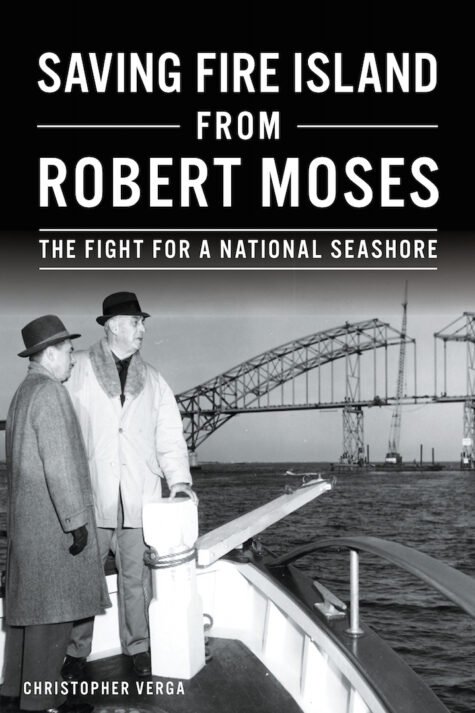

“Saving Fire Island from Robert Moses: The Fight for a National Seashore”

By Christopher Verga

Arcadia Publishing and The History Press $21.99

It may take a village to raise a child, but it took 17 Fire Island communities to take down Robert Moses. It was no small task to tackle the power broker who ruled the roadways with a finger snap in the ‘60s, but Moses had his hands full when he set his mind on a four-lane highway through the barrier beaches of the South Shore. When you consider his penchant for roads and causeways, you might say Moses was a driven man. I mean that literally – having never bothered getting a driver’s license, he was chauffeured around by state-provided handlers.

It is clear that author Christopher Verga, a professor at Suffolk County Community College, is no fan of urban renewal in the hands of Robert Moses.

He tells of the master builder who bulldozed entire New York City neighborhoods and left residents – animals, he called them, scrambling to find new housing. When local politicians tried to fight for their supporters who objected to the great builder’s plans, Moses turned to his more powerful cronies to outvote them. Though not trained as an engineer, architect or urban planner, Moses controlled millions of dollars for his projects. He also had a firm grip on the press.

In 1964 when rookie reporter Karl Grossman criticized him for ill treatment of civil rights activists, Moses had him fired from his job at the Babylon Town Leader. His publisher was succinct and to the point: “Mr. Moses called and is very upset with you. You’re fired.” Not to worry about Grossman, he went on to become an award-winning investigative reporter and a professor of journalism at SUNY Old Westbury and is a columnist with this publication.

Verga traces Moses’ decades-long obsession to build a “Fire Island Parkway,” from the 1938 hurricane to 1962, when the island was hit with a nor’easter that destroyed 100 homes across the South Shore Coast. Excessive flooding from winter storms worried residents, and they began to reconsider his proposal that claimed a highway would anchor shifting and eroding dunes. This claim proved to be false when Grossman once again called him out. He reported that “during the twilight hours, Moses would routinely secretly replace sand that had eroded along the [existing] Ocean Parkway” that he wanted to extend into Fire Island. Still Moses continued to use his power, politicians and special interest groups to play his highway forward while keeping his intentions from the public.

Though each Fire Island community had its own unique identity – Ocean Beach, outgoing and friendly; Point O’ Woods, more old money and conservative; Saltaire, considered exclusive and nouveau rich; Cherry Grove, a growing gay community – but when it came to their island’s pristine beaches, its laid back, get-away-from-it-all way of life, they spoke with one voice: Take your parkway and go, Mr. Moses! But how could they fight thepowerhouse Moses?

Verga tells a compelling tale of how Maurice Barbash, Fire Island resident and builder of Dunewood, and lawyer Irving Like, spearheaded the citizens’ committee to designate Fire Island as a National Seashore. Grassroots roots activism spread across the island. The League of Women Voters got involved. Environmental mainland organizations that were beginning to gain traction had their say in favor of keeping Fire Island the way it was and had always been. No cars. No fumes spoiling the clean air. Residents wrote letters. They had meetings. They made phone calls – no cell phones then – landline only. They roused public opinion to their side.

It wasn’t only the locals Moses had to contend with. He had Laurance Rockefeller, founder of the American Conservation Association and Interior Secretary Stewart Udall, who believed a parkway across Fire Island would be detrimental tothe its natural environment.

His stunning defeat came in 1964 when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed a bill that created the National Seashore and designated 33 miles of Fire Island as a national park. Public outcry pressured him to resign from his five state posts. Moses was done. Moses was toast. Fire Island definitely was not his Promised Land.

Included in the text are photos from libraries, archives and Verga’s personal collection. One snapshot shows two nuns in full habit with their black skirts hiked up clamming in the South Shore waters. Only on Fire Island.