Fire Island Taxi Driver:

Recollections of Summers on the Beach

at Fabulous Fire Island, NY, 1960-64

by Peter Christian Olsen

Fiction/Lucas Parks Books

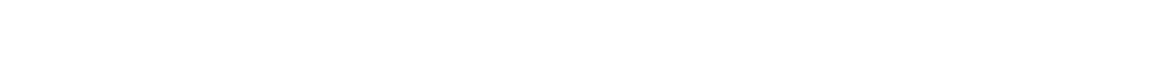

Beachside taxis are now a footnote in Fire Island history. They were discontinued after Congress passed, and President Lyndon Johnson signed an act declaring Fire Island a national seashore.

Retired now, Peter Olsen looks back on his college days as a “Fire Island Taxi Driver” for White Cap Taxi. But years before he took the wheel of one of their “ancient barely functional” four-wheel-drive revamped relics from WWII, he had spent his summers on the island.

A passenger in a stripped-down Model A Ford, the cab cut “to make it a convertible. When started, the cab “hummed like a food processor,” but once it got going, “the buggy… jumped three feet into thin air,” leaving Olsen face down in the sand, water washing over him. Rather than a deterrent, the ride fired his dream to take the wheel along the beachfront one day.

Olsen’s chance came when the 1960s rolled in.

Overcoming the obstacles of his interview (he never drove on the sand) and getting his New York State chauffeur’s license (he lived in New Jersey), the author landed the job that helped him pay his way through graduate school.

Dispatcher-to-driver, via short-wave radio, he moved folks from one Fire Island beachfront community to the other, learning on the fly the designated pickup spots. Show up at the wrong place, and he’d get an earful from co-owner Roger, whose big mitt (after wiping his lunch on his shirt) felt like shaking hands with a “freshly oiled baseball glove.”

On the job, there was more to learn than geography. For example, there was the how-to of taxi maintenance in damp, humid weather (a blanket over the hood at night), getting the car to start with salt spray on the engine, and pitching in at the office.

Roger warned, “Be on your toes.”

He might get a call from a celebrity searching for a place to eat or from folks looking for a celebrity at Fire Island Pines or Cherry Grove restaurants. The Grove attracted visitors who wanted to people-watch more than they wanted a meal.

The rules for the drivers “came mostly as mandates” from owners Roger and Everet:

“Don’t run over sunbathers if you can possibly avoid it.”

“Never try to cheat the bosses out of money.” (There were no meters, and drivers set their own rates, depending on how many and how drunk passengers might be.)

According to them, “‘higher learning confused one’s sense of responsibility, and college students were the most confused of all.’”

It stood to reason then (their reason) that Olsen got the most dilapidated cab to drive.

Competition amongst the drivers ran high, especially with the “interlopers and intruders,” the part-time weekend drivers. Olsen describes a gorgeous hunk with white teeth and a beautiful smile that the gay patrons loved.

“God, how I hated him.”

Camaraderie? Not so much.

Chapter captions feature quotes from William Shakespeare to the notorious Travis Bickle, of “Taxi Driver.” Man-talk like “womanizing,” “horny chicks,” and “lezzies,” pulled me back to times gone by. Good riddance to those times.

There are some repetitive references and overly explained, lengthy dialogue that would benefit from editing. But keep reading; there’s humor in the book—his dating experiences are a hoot—and interesting episodes, such as an unexpected conversation with Edward Albee, one of the author’s idols.

The chapter “Queer Culture” introduces readers to Cherry Grove’s and The Pine’s history going back to the 1920s, a place where gay men “could feel at home without being too far from home.” But more telling is Olsen’s personal observations and reflections on the gay community he witnessed as a taxi driver.

Having grown up “under the influence of homophobes… shy and reserved by nature,” he’s uncomfortable “in the fantasy world with the inhabitants better looking, better educated and with more self-esteem than I could muster.”

I was taken with the author’s honesty and his ambivalence. On the one hand, he appreciates the many LBGTQ artistic contributions to the culture at large—he even wonders if he were gay, would he acquire some of their talents. And yet he’s repulsed by their sexuality “because I feared I might have the same tendencies myself.” It’s pretty heady stuff for a young man, to admit.

By the end of the day (and the book), Olsen realizes that “sexuality is only a small part of one’s personality and character.” This is a valuable takeaway from an “ideal summer job.”