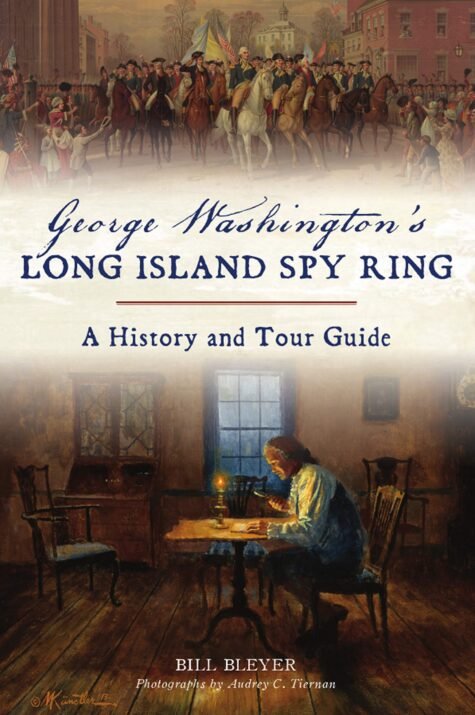

George Washington’s Long Island Spy RingA History and Tour GuideBy Bill BleyerNonfiction – History Press Agents and informants, traitors and trysts seduce our imagination in novels, movies and television; but if you want the real deal on spies, tuck into a copy of prize-winning journalist Bill Bleyer’s “George Washington’s Long Island Spy Ring, A History and Tour Guide.”Bleyer challenges previous authors whose books about Washington’s spy ring (aka Culper Spy Ring) have strayed from the truth and transformed “anecdotal information and legends into facts.” He supports his text with hundreds of footnotes and credits, transcripts of letters, code books and ledgers. Photographer Audrey C. Tiernen supplies color plates of landmark homes and period furnishings, giving readers a flavor of what home life might have looked like back in the day.Organized by spymaster Major Benjamin Tallmadge and General George Washington, the Culper Spy Ring operated between New York City (British headquarters), Long Island and Connecticut from 1778 to 1783 during the American Revolution. Mission: to provide Washington information on British Army operations.Washington knew full the “importance of military intelligence.” It started when he was serving in the French and Indian War (1755) and a force of militia was “ambushed and nearly annihilated” in a surprise attack. Later on, during the Revolution, knowing of the high-level British espionage operations he said, “There is one evil I dread, and that is, their spies.”We had our own spies to contend with and Bleyer gives the skinny on Nathan Hale, a hero I recall from my high school American history. But as the author credits Kenneth Daigler in “Spies,” Hale was history in more ways than one. He was a “lousy spy.” He conducted his solo mission in ways “horrible by both intelligence and commonsense standards.” He cites that Hale’s “…strong sense of personal integrity … made it difficult for him to lie effectively.” A quality, it seems to this reader, essential for that particular vocation.From Setauket to Manhattan and back to the Connecticut shore on whaleboats, patriots like Abraham Woodhull, Robert Townsend and Caleb Brewster passed secret links and cyphered messages warning General Washington of British troopships and where they would be dispatched, the ammunition the ships carried and the morale of their soldiers (at times up, at times down).Another agent was said to have been Anna Strong – they weren’t all men, surprise, surprise – who hung out her laundry in a pattern that would tell spies where they should rendezvous. If she pinned a black petticoat to her Long Island wash line, a spy in Connecticut (using a telescope) would know that a compatriot would be arriving to retrieve or drop off a message for him. An addition of white hankies indicated at which of six coves he would be waiting.Family historian Kate Strong even devoted a chapter in her own penned book to defend Anna’s clothesline (its certainty had come into question), claiming she had “scraps of paper, deeds, journals in her possession, and well as documents she saw or was told about…” According to Bleyer, Strong’s narrative doesn’t hold up (even if her clothesline did) and he challenges historians who have accepted the story “without skepticism.” Bleyer notes that her clothesline was not near the beach, and that the lay of the land and the distance between Long Island Sound and Connecticut, “ignores the curvature of the Earth that would thwart even modern telescopes.”For this reviewer, putting out the wash and saving your country at the same time is multitasking at its best. I for one was sorry to see Bleyer’s investigative eye take that story down and dispatch it to “local legend.”It cost money to run a spy ring, and Washington was often beset by ways in which to fund the operation. Bleyer details the $50 per month one agent received plus a $500 allowance to pay informants. Another was paid $946 for “secret services.” At war’s end one agent submitted a bill just over £500 ($94,000 in 2020). It makes for interesting reading to discover what expenses Washington saw fit to pay and those he did not, and why. As is when the Brits finally decamped New York City in 1783, how the general assessed the Culper Spy Ring’s contribution to the war effort.And that’s what Bleyer wants folks to do, read the book and “make up their own minds.”

George Washington’s Long Island Spy RingA History and Tour GuideBy Bill BleyerNonfiction – History Press Agents and informants, traitors and trysts seduce our imagination in novels, movies and television; but if you want the real deal on spies, tuck into a copy of prize-winning journalist Bill Bleyer’s “George Washington’s Long Island Spy Ring, A History and Tour Guide.”Bleyer challenges previous authors whose books about Washington’s spy ring (aka Culper Spy Ring) have strayed from the truth and transformed “anecdotal information and legends into facts.” He supports his text with hundreds of footnotes and credits, transcripts of letters, code books and ledgers. Photographer Audrey C. Tiernen supplies color plates of landmark homes and period furnishings, giving readers a flavor of what home life might have looked like back in the day.Organized by spymaster Major Benjamin Tallmadge and General George Washington, the Culper Spy Ring operated between New York City (British headquarters), Long Island and Connecticut from 1778 to 1783 during the American Revolution. Mission: to provide Washington information on British Army operations.Washington knew full the “importance of military intelligence.” It started when he was serving in the French and Indian War (1755) and a force of militia was “ambushed and nearly annihilated” in a surprise attack. Later on, during the Revolution, knowing of the high-level British espionage operations he said, “There is one evil I dread, and that is, their spies.”We had our own spies to contend with and Bleyer gives the skinny on Nathan Hale, a hero I recall from my high school American history. But as the author credits Kenneth Daigler in “Spies,” Hale was history in more ways than one. He was a “lousy spy.” He conducted his solo mission in ways “horrible by both intelligence and commonsense standards.” He cites that Hale’s “…strong sense of personal integrity … made it difficult for him to lie effectively.” A quality, it seems to this reader, essential for that particular vocation.From Setauket to Manhattan and back to the Connecticut shore on whaleboats, patriots like Abraham Woodhull, Robert Townsend and Caleb Brewster passed secret links and cyphered messages warning General Washington of British troopships and where they would be dispatched, the ammunition the ships carried and the morale of their soldiers (at times up, at times down).Another agent was said to have been Anna Strong – they weren’t all men, surprise, surprise – who hung out her laundry in a pattern that would tell spies where they should rendezvous. If she pinned a black petticoat to her Long Island wash line, a spy in Connecticut (using a telescope) would know that a compatriot would be arriving to retrieve or drop off a message for him. An addition of white hankies indicated at which of six coves he would be waiting.Family historian Kate Strong even devoted a chapter in her own penned book to defend Anna’s clothesline (its certainty had come into question), claiming she had “scraps of paper, deeds, journals in her possession, and well as documents she saw or was told about…” According to Bleyer, Strong’s narrative doesn’t hold up (even if her clothesline did) and he challenges historians who have accepted the story “without skepticism.” Bleyer notes that her clothesline was not near the beach, and that the lay of the land and the distance between Long Island Sound and Connecticut, “ignores the curvature of the Earth that would thwart even modern telescopes.”For this reviewer, putting out the wash and saving your country at the same time is multitasking at its best. I for one was sorry to see Bleyer’s investigative eye take that story down and dispatch it to “local legend.”It cost money to run a spy ring, and Washington was often beset by ways in which to fund the operation. Bleyer details the $50 per month one agent received plus a $500 allowance to pay informants. Another was paid $946 for “secret services.” At war’s end one agent submitted a bill just over £500 ($94,000 in 2020). It makes for interesting reading to discover what expenses Washington saw fit to pay and those he did not, and why. As is when the Brits finally decamped New York City in 1783, how the general assessed the Culper Spy Ring’s contribution to the war effort.And that’s what Bleyer wants folks to do, read the book and “make up their own minds.”