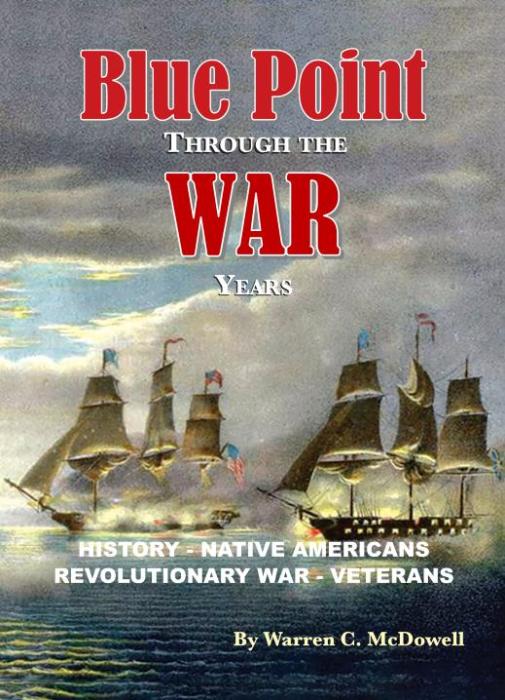

By Rita Plush“Long Island and World War I”By Richard F. WelchNon-fiction, Arcadia Press $21.99An enthusiastic student of World War I, the book’s author Richard F. Welch went on to earn a doctorate in American history. His interest came full circle when he signed on as curator of the 2017 centennial exhibition of World War I, sponsored by the Suffolk County Historical Society, and decided to further his research and turn the project into a book. Readers will be glad he did.If fun and sun come to mind at the mention of Long Island there’s good reason for it, its unspoiled beaches rank among the most beautiful in the U.S. But during World War I the shores of Nassau and Suffolk counties were no day at the beach. Long Islanders kept more serious company then, producing everything from torpedoes, to observation balloons, to training Home Guards (men too old to serve in the armed forces but who could help at home) in their efforts to serve their nation.“In Long Island and World War I,” author/ historian, Welch, a native Long Islander, explains the area’s gradual support of the different relief agencies, to doubling down its efforts and marshaling its citizens and resources, when the conflict in Europe escalated.In order to feed the troops both over here and over there, farmers and citizens alike were encouraged to “Plant, Plant, Plant.” The counties set up local canneries and the village of Stony Brook, notes the author’s careful research, sent 20,000 pounds of jam to France.Patriotism was surely in the air, but should citizens object to the U.S. breaking diplomatic relations with Germany and entering the war, former President Theodore Roosevelt was on hand to press upon young recruits the value of “manhood and courage.” Men who were unwilling to be soldiers were sissies and not entitled to vote.Soldiering aside, in 1918, women were picketing the White House with their own call to arms. Editorials such as the one in Huntington’s Long Islander stating the fact that “women are just as patriotic, filled with as high ideals, understand the vital political issues of the day and the country’s needs, and are making just as great sacrifices as the men for the welfare of the nation,” helped millions of American women make for the polls.As more young men entered the armed forces, Long Island boasted 16 new training centers “constructed out of scratch” to prepare recruits for overseas combat. Camp Upton in Yaphank was the largest, and was used as a convalescent and rehabilitation hospital for wounded veterans after the war and again after World War II. It later became the site of the Brookhaven National Laboratory.If you ever thought your ride on the Long Island Rail Road was crowded, back then you might have shared your commute with torpedoes. Shipped from Brooklyn, they were sent to Sag Harbor via the railroad and loaded onto launches for testing in Noyac and Shelter Island Bay. But it wasn’t all work and no play for the traineesNearby restaurants, movie theaters and hotels welcomed the young recruits and the business they brought with them. Most of them, away from home for the first time, their excessive drinking and the character of “the visitors” with whom they came in contact worried army officials. There were raids, and the “comely proprietress” of the White Oak Inn in Medford was arrested for selling liquor to the soldiers. She was sentenced to 30 days in jail for the offense. (It was against the law then to serve or sell servicemen alcohol.) Spirits and fast company were not the only challenges some recruits faced, author Welch points out.Segregation in the military was still very much an issue during the First World War, and this book does not shy away from it. However this history on Long Island also notes that in spite of segregation there were blacks who advanced, and in 1918, Albert W. Sells, a Stony Brook resident, wrote to a friend, “I am one of the first colored officers made out of the ranks.”Once the war was over, Long Island took care of its own. Branches of the Bureau of Returning Soldiers were set up throughout the region, helping train and find jobs for the veterans. Freeport founded the Social Welfare Association of Nassau County to assist the injured or maimed who had given over and beyond to their country.Both military and Long Island history enthusiasts alike will enjoy the information this concise, yet detailed volume has to offer. Its publication as we approach the century milestone of the conclusion of World War 1 is most timely indeed.

By Rita Plush“Long Island and World War I”By Richard F. WelchNon-fiction, Arcadia Press $21.99An enthusiastic student of World War I, the book’s author Richard F. Welch went on to earn a doctorate in American history. His interest came full circle when he signed on as curator of the 2017 centennial exhibition of World War I, sponsored by the Suffolk County Historical Society, and decided to further his research and turn the project into a book. Readers will be glad he did.If fun and sun come to mind at the mention of Long Island there’s good reason for it, its unspoiled beaches rank among the most beautiful in the U.S. But during World War I the shores of Nassau and Suffolk counties were no day at the beach. Long Islanders kept more serious company then, producing everything from torpedoes, to observation balloons, to training Home Guards (men too old to serve in the armed forces but who could help at home) in their efforts to serve their nation.“In Long Island and World War I,” author/ historian, Welch, a native Long Islander, explains the area’s gradual support of the different relief agencies, to doubling down its efforts and marshaling its citizens and resources, when the conflict in Europe escalated.In order to feed the troops both over here and over there, farmers and citizens alike were encouraged to “Plant, Plant, Plant.” The counties set up local canneries and the village of Stony Brook, notes the author’s careful research, sent 20,000 pounds of jam to France.Patriotism was surely in the air, but should citizens object to the U.S. breaking diplomatic relations with Germany and entering the war, former President Theodore Roosevelt was on hand to press upon young recruits the value of “manhood and courage.” Men who were unwilling to be soldiers were sissies and not entitled to vote.Soldiering aside, in 1918, women were picketing the White House with their own call to arms. Editorials such as the one in Huntington’s Long Islander stating the fact that “women are just as patriotic, filled with as high ideals, understand the vital political issues of the day and the country’s needs, and are making just as great sacrifices as the men for the welfare of the nation,” helped millions of American women make for the polls.As more young men entered the armed forces, Long Island boasted 16 new training centers “constructed out of scratch” to prepare recruits for overseas combat. Camp Upton in Yaphank was the largest, and was used as a convalescent and rehabilitation hospital for wounded veterans after the war and again after World War II. It later became the site of the Brookhaven National Laboratory.If you ever thought your ride on the Long Island Rail Road was crowded, back then you might have shared your commute with torpedoes. Shipped from Brooklyn, they were sent to Sag Harbor via the railroad and loaded onto launches for testing in Noyac and Shelter Island Bay. But it wasn’t all work and no play for the traineesNearby restaurants, movie theaters and hotels welcomed the young recruits and the business they brought with them. Most of them, away from home for the first time, their excessive drinking and the character of “the visitors” with whom they came in contact worried army officials. There were raids, and the “comely proprietress” of the White Oak Inn in Medford was arrested for selling liquor to the soldiers. She was sentenced to 30 days in jail for the offense. (It was against the law then to serve or sell servicemen alcohol.) Spirits and fast company were not the only challenges some recruits faced, author Welch points out.Segregation in the military was still very much an issue during the First World War, and this book does not shy away from it. However this history on Long Island also notes that in spite of segregation there were blacks who advanced, and in 1918, Albert W. Sells, a Stony Brook resident, wrote to a friend, “I am one of the first colored officers made out of the ranks.”Once the war was over, Long Island took care of its own. Branches of the Bureau of Returning Soldiers were set up throughout the region, helping train and find jobs for the veterans. Freeport founded the Social Welfare Association of Nassau County to assist the injured or maimed who had given over and beyond to their country.Both military and Long Island history enthusiasts alike will enjoy the information this concise, yet detailed volume has to offer. Its publication as we approach the century milestone of the conclusion of World War 1 is most timely indeed.