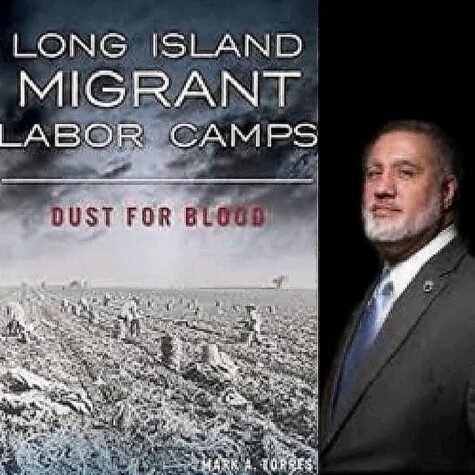

Long Island Migrant Labor Camps: Dust for BloodBy Mark A. TorresNon-FictionThe History Press Just 100 miles away from the riches of New York City, in the seemingly idyllic setting of Eastern Long Island, thousands of migrant workers looking for a decent wage and a place to live were cheated out of their pay and subjected to horrifying working conditions in migrant labor camps during World War II, and for decades after.Mark Torres, Nassau County resident, labor and employment attorney and advocate for nonunionized workers, sheds a grim light on both local and national governments who either turned a blind eye to the migrants’ plight, or were unaware of the injustice done to those who had but few advocating for them.The labor shortage caused by citizens going off to war left an urgency for farm workers to harvest the roughly 6 million bushels of Suffolk County’s potatoes. Backbreaking “stoop labor” it was called. Workers hunched over or crawled on their knees along the field to retrieve potatoes fallen from the vine. It wasn’t only potatoes the migrants collected. A farm in Shelter Island produced 1 million pounds of lima beans per season and 20 tons of cauliflower, all requiring of field labor.Polish and Chinese immigrants worked the fields along with Mexicans brought in to gather the crops. Laborers from the south and workers from the island of Jamaica riled Southold locals and the notion that “several hundred colored men from the South [were] hired to work in Suffolk.” Labor laws to protect the migrant workers? There were none. Not in Suffolk County or in any camp across the nation where the workers lived in crowded, dirty, hovel-like buildings.Reports one journalist who had toured the Suffolk sites: “Shoved off in the back country were migrant shacks that have no plumbing or indoor cooking facilities, that house up to 60 men, women and children, that swarm with flies and are slick with grease.”The school at the Cutchogue labor camp, the largest and most “notorious” of the 120 Suffolk Country camps housing close to 2,000 workers, fared no better.“The putrid stench of raw sewage” leaked just outside the door of her classroom, writes Helen Wright Prince in her memoir, “My Migrant Labor Camp School.” A space heater used to heat the room once exploded when she tried to light it. When Ms. Prince advocated for the children to the trustee of the Eastern Suffolk Cooperative (under whose aegis the camps were held), said the trustee, “But Helen, you don’t have to teach them anything. You just have to keep order.”Torres covers, or rather uncovers, the “abysmal” slum-like conditions of the labor camps, detailing how the workers were exploited by their own crew leaders, who overcharged them for food and housing and all manner of daily necessities, including blankets, rendering generations forever in debt.There were those however, who did care and wanted to help. Torres calls them “Better Angels,” and profiles the work of people like Arthur Cullen Bryant, Mary Chase Stone and Morton Silverstein.Edward R. Murrow broadcast “Harvest of Shame,” a documentary that chronicled the plight of migrant farm workers who traveled from Florida up through New York and the west coast, urging “wage, health and housing reforms.” Released on Thanksgiving 1960 with the hope of waking up a well-fed nation to the conditions the migrants faced, the film may have roused our fellow citizens for the moment, but they went right back to sleep. When journalist Harvey Aaronson visited the Cutchogue camp afterward, he found little had changed.It took more than half a century for what Torres considers “the shame of the nation,” where industry and profit “were more important than human life,” to come to an end. Sadly, its demise was due more to a shift in technology, “farming ideology” and real estate going sky high, that led to a decline in production and the need for manpower, rather than the populous banding together to dismantle a “broken system” that ruined so many lives for so many years.But there is hope. On Jan. 1, 2021, New York State passed the Farm Laborers Fair Labor Practices Act that sets standards for farm workers in the state and allows farm workers to join labor unions. The bad news is, the agricultural industry is challenging the law.The plight of migrant farm workers is far from over. Torres urges readers to connect with local or national groups to advocate for those who “work so hard to help feed our nation.” And I urge folks to read this book.

Long Island Migrant Labor Camps: Dust for BloodBy Mark A. TorresNon-FictionThe History Press Just 100 miles away from the riches of New York City, in the seemingly idyllic setting of Eastern Long Island, thousands of migrant workers looking for a decent wage and a place to live were cheated out of their pay and subjected to horrifying working conditions in migrant labor camps during World War II, and for decades after.Mark Torres, Nassau County resident, labor and employment attorney and advocate for nonunionized workers, sheds a grim light on both local and national governments who either turned a blind eye to the migrants’ plight, or were unaware of the injustice done to those who had but few advocating for them.The labor shortage caused by citizens going off to war left an urgency for farm workers to harvest the roughly 6 million bushels of Suffolk County’s potatoes. Backbreaking “stoop labor” it was called. Workers hunched over or crawled on their knees along the field to retrieve potatoes fallen from the vine. It wasn’t only potatoes the migrants collected. A farm in Shelter Island produced 1 million pounds of lima beans per season and 20 tons of cauliflower, all requiring of field labor.Polish and Chinese immigrants worked the fields along with Mexicans brought in to gather the crops. Laborers from the south and workers from the island of Jamaica riled Southold locals and the notion that “several hundred colored men from the South [were] hired to work in Suffolk.” Labor laws to protect the migrant workers? There were none. Not in Suffolk County or in any camp across the nation where the workers lived in crowded, dirty, hovel-like buildings.Reports one journalist who had toured the Suffolk sites: “Shoved off in the back country were migrant shacks that have no plumbing or indoor cooking facilities, that house up to 60 men, women and children, that swarm with flies and are slick with grease.”The school at the Cutchogue labor camp, the largest and most “notorious” of the 120 Suffolk Country camps housing close to 2,000 workers, fared no better.“The putrid stench of raw sewage” leaked just outside the door of her classroom, writes Helen Wright Prince in her memoir, “My Migrant Labor Camp School.” A space heater used to heat the room once exploded when she tried to light it. When Ms. Prince advocated for the children to the trustee of the Eastern Suffolk Cooperative (under whose aegis the camps were held), said the trustee, “But Helen, you don’t have to teach them anything. You just have to keep order.”Torres covers, or rather uncovers, the “abysmal” slum-like conditions of the labor camps, detailing how the workers were exploited by their own crew leaders, who overcharged them for food and housing and all manner of daily necessities, including blankets, rendering generations forever in debt.There were those however, who did care and wanted to help. Torres calls them “Better Angels,” and profiles the work of people like Arthur Cullen Bryant, Mary Chase Stone and Morton Silverstein.Edward R. Murrow broadcast “Harvest of Shame,” a documentary that chronicled the plight of migrant farm workers who traveled from Florida up through New York and the west coast, urging “wage, health and housing reforms.” Released on Thanksgiving 1960 with the hope of waking up a well-fed nation to the conditions the migrants faced, the film may have roused our fellow citizens for the moment, but they went right back to sleep. When journalist Harvey Aaronson visited the Cutchogue camp afterward, he found little had changed.It took more than half a century for what Torres considers “the shame of the nation,” where industry and profit “were more important than human life,” to come to an end. Sadly, its demise was due more to a shift in technology, “farming ideology” and real estate going sky high, that led to a decline in production and the need for manpower, rather than the populous banding together to dismantle a “broken system” that ruined so many lives for so many years.But there is hope. On Jan. 1, 2021, New York State passed the Farm Laborers Fair Labor Practices Act that sets standards for farm workers in the state and allows farm workers to join labor unions. The bad news is, the agricultural industry is challenging the law.The plight of migrant farm workers is far from over. Torres urges readers to connect with local or national groups to advocate for those who “work so hard to help feed our nation.” And I urge folks to read this book.