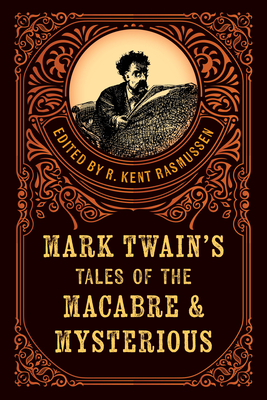

“Mark Twain’s Tales of the

Macabre & Mysterious”

Edited by R. Kent Rasmussen

Fiction

Lyons Press

I was curious about how Samuel Clemens came up with Mark Twain as his pen name, so I did some internet sleuthing. “Mark Twain” is a nautical term (twain means two) for a measured river depth of two fathoms, the safe depth for a steamboat to pass. As a steamboat pilot, Clemens must have heard sailors cry out, “Mark Twain!” many times. When he worked as a newspaper reporter years later, he began signing his name thus.

In addition to novels about daring young boys, as chronicled in “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn,” Mark Twain wrote short stories, news articles, sketches, travel narratives, and books, but his horror stories are less discussed.

A recognized world authority on Twain, R Kent Rasmussen designed this 32-story collection—some shortened and excerpted from his novels—to highlight Twain’s “least-known and unjustly overlooked writings.”

The editor’s brief forward to each entry connects readers to the tale’s origin, allowing for a deeper understanding of the story and a peek into the mind of the man Ernest Hemmingway called “…the Lincoln of our literature.”

Take your pick of the six sections: Tales Spooky and Grisly; Unpleasant Places; Remarkable Characters; Curious and Strange Obsessions; Worlds Remote In Time & Space” and Ironic Twists; and Clever Deceptions, and you’ll find the wild imagination, sharp wit and compelling dialogue that brought these stories to the page.

In “Cross of The Mysterious Avenger,” Twain revisits his hometown of Hannibal, Missouri, after decades of absence and meets up with a carpenter who had mesmerized him with thrilling stories. He’d hunted down an entire family, “murdered thirty human beings,” with the same bowie knife because one of them had killed his wife 20 years before. When Twain discovers the tale a fiction, he feels duped and ashamed that this man who “had so lately been a majestic and incomparable hero” was nothing but a “poor foolish exposed humbug.” Macabre, maybe, but a spot-on take on you can’t—or shouldn’t—go home again.

If you have ever thought about how things used to be, you should visit “Neglected Graveyards.” There, a 30-year-old skeleton reminisces about the good times and gripes about the bad

When he was “laid down out in the country, out in the breezy flowery, grand old woods, and the lazy winds gossiped with the leaves. Ah, it was worth ten years of a man’s life to be dead then.” The graveyard was in the best part of town and kept up. Now, all is rotting: tombstones this way and that; fences are falling apart. “Vermin gnawing” at his shroud, the poor skeleton can’t keep “skull and bones together.” Worse, his descendants don’t call, don’t write, and no longer visit his grave. At once funny and sad (Parents of grown children, can you relate?), the editor explains that Twain wrote the sketch to focus on a neglected Buffalo cemetery and “helped launch a cemetery reform movement.”

“Incomprehensible” was Twain’s opinion of the teachings of Mary Baker Eddy, the American founder of Christian Science. His thoughts are found in “Nothing Exists but Mind,” taken from his nonfiction book, “Christian Science,” a little-read tome he wrote more than a century ago.

A man falls off a cliff while traveling and breaks “some arms and legs and one thing or another.” He’s stranded in an obscure town where a Christian Science doctor “who could treat anything” is the only one who can patch him up. The man laments his great pain, but the doctor, “resolute jaw and a Roman beak,” insists that “pain is unreal; hence, pain cannot hurt.” Feelings don’t exist either, so we can’t speak of them. The only real and relevant thing in our lives is the “mind.” Thrown into the mix is a horse doctor, bringing the exaggerated dialogue and confusion up a notch (or down) to comedy bordering on burlesque.

Though Twain had strong reservations about Christian Science as a religion, he did concede that it “was at least possible… that the human mind is capable of healing the body.”

And it’s more than possible that readers will enjoy this very readable collection during the Halloween season.

The “entirely original” illustrations Rasmussen provides are his work—with the help of “Microsoft Bing’s online Image Creator program… and their immense data bank of digitized pictures.” While many worry about the risks and dangers of artificial intelligence, Rasmussen applauds “the incredible advances in AI technology.” To my eye, though the illustrations are unique, the artworks are a bit modern-looking for these age-old stories.