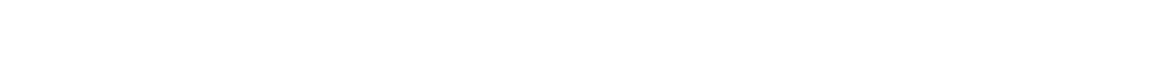

Norman Lear: His Life & Times

by Tripp Whetsell

Biography/Applause

When author Tripp Whetsell of Westhampton Beach was growing up in the 70’s and 80’s, he watched Norman Lear’s sitcoms. He credits his subject with not only a brilliant wit, but as an escape “from a childhood marred by learning disabilities.” Whetsell confesses to the “attention span of a gnat,” but when it came to All in the Family—Lear’s most remembered sitcom and based on the British, Till Death Do Us Part—he had “laser focus.”

Lear too had problems as a youngster, and for a man whose life’s calling was to make people laugh, there was nothing funny about his childhood.

Whetsell notes Lear’s father was a bigot—Archie Bunker anyone?—with big dreams and bravado, but little in the way of providing for his family. His “cold and indifferent” mother brought little to the nurturing table. When her son was elected into the first Television Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1953 (along with Lucile Ball and Edward R. Murrow), Jeanette said, “Listen, if that’s what they want, who am I to say?” Archie and Edith were based on Lear’s parents; “Meathead,” “Dingbat,” and “Stifle yourself,” came right out of Herman Lear’s mouth.

Lear not only “survived a childhood that was marred by pain, poverty, and often desperation,” he turned it into TV gold. And perhaps in the transition, a catharsis for his troubled youth.

King of the small screen, he made the boob tube big when he took on real people with real problems: Maude’s abortion at 47; teen sex, when Julie’s boyfriend puts on the pressure in One Day at d a Time; Edith’s attempted rape in All in the Family. Lear found the funny in race, class, and sexuality – hot-button topics that, for years, network heads thought were too taboo for TV.

Maude (Bea Arthur, Lear’s “favorite performer,”) introduces herself to Florida, a Black woman who has come to interview for a maid position: “You can call me Maude, and my daughter, Carol. And what would you like us to call you?”

“You can call me Mrs. Evans,” Florida deadpans, typifying how Florida would often have the last word putting Maude in her liberal place.

There were conflicts offscreen as well. Sally Struthers—Gloria, on All in the Family—complained that her clothes were typecasting her as a “plain, average American girl” and would prevent her from getting other roles. But the “worst strife by far was the ongoing hostility between O’Connor and Norman… it sort of dominated the whole atmosphere.”

This reviewer prefers a lighter mood and Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman—MH2 to the cast and company, and a satire on soaps and a cult favorite—fit that bill just fine. As the ever-cheerful and melancholy midwestern housewife, Louise Lasser was a hoot. When coach Leroy drowned in a bowl of Mary’s chicken soup and she thought she should be arrested for manslaughter? And her grandfather was the flasher. LOL as far as I was concerned.

Author Whetsell does a deep dive into the life of Lear, and comes up with inside intrigues that will fascinate anyone who has ever turned on a TV. Yes, the book brims with praise and admiration—Lear is a hero of Whetsell’s after all. Yet the author turns an objective eye to Lear’s less-than-perfect life.

Not every script he put his hand to was a star; Sunday Dinner filmed in Great Neck; All’s Fair and The Hot l Baltimore didn’t last long. He had two marriage flops as well. His second marriage was to Frances Loeb, and it ended in a divorce settlement that cost him between $100–$112 million—over $260 million today—and, in 1986, it was one of the largest recorded settlements for a marital breakup.

But Lear didn’t balk at big payouts when he turned his social consciousness to philanthropy and founded People for the American Way, a progressive advocacy group. In 1982 he fought Jerry Falwell and the rise of the political right with I Love Liberty, an all-star event in which Robin Williams delivered a monologue as the American flag. The Lear Family Foundation continues to support civil liberties, education, the environment, health, and youth initiatives.

Lear’s decades of outstanding TV and movie work won him the arts’ most coveted Peabody award. He garnered six Emmys and was the oldest person (98) to ever win two, back-to-back.

The man Whetsell describes as “The Energizer Bunny, who didn’t know the meaning of rest,” died in 2023 at the age of 101.

Tripp Whetsell is a well-known entertainment journalist and adjunct professor at Emerson College. He interviewed Lear for TV Guide in 2011 to mark All in the Family’s 40th anniversary and featured Lear in his previous book, The Improv: An Oral History of the Comedy Club That Revolutionized Stand-Up.