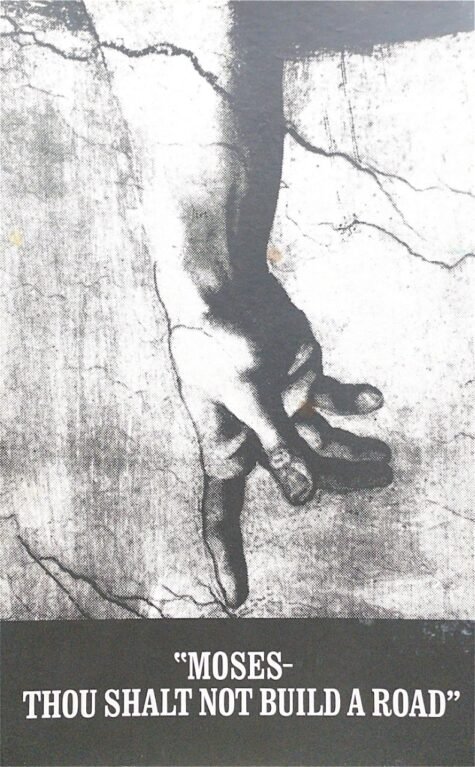

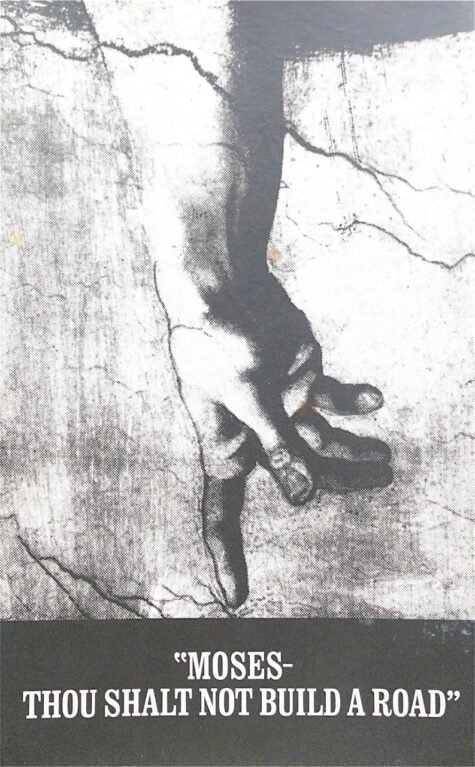

Author of “Saving Fire Island from Robert Moses,” Christopher Verga, delivered a virtual lecture, hosted by Fire Island School Adult Education Program, on Thursday, July 15, giving those who tuned in a presentation about the fight for a national seashore.He spoke about Robert Moses’s decades long vision to create a four-lane highway cutting through the 17 individual communities and barrier beaches that establish Fire Island. Verga says this theoretical highway would have connected to Ocean Parkway, then run to Montauk Point, though Moses was not trained as an engineer, architect or urban planner.Verga dove into the beginnings and endings of Moses’s “master builder” career, and it was immediately clear that he is no fan of Robert Moses.“Moses’s projects gave little credence to environmental impacts,” Verga said. “Like closing inlets … now this is why we struggle with brown tide. If the inlets were open, high tide would naturally flush out the back bay. We’re still dealing with the ramifications of Robert Moses to this day.”Severe storms and flooding worried residents on and off the island, and Moses’s highway proposals were reconsidered as he claimed throughout the 1950s that they would anchor shifting and eroding dunes.The lecturer explained that first district Congressman Stuyvesant Wainright was the first to propose Fire Island be recognized as a national park. Moses labeled Wainwright an elitist, killing his national park proposal and his reelection.Verga said from this point in history, in a formula to activism, Dunewood’s own Maurice Barbash, home builder and environmental activist, was instrumental in blocking the project. “Barbash was inspired by landscapes and individualistic communities not dependent on cars,” Verga said.Barbash contacted every group that would benefit from the preservation of Fire Island, including the chamber of commerce, sports and fishing groups, and the ferry companies. He understood the importance of contacting elected officials and had artists create awareness posters. He also stressed the importance of withdrawing financial support from pro-highway candidates. This grassroots activism helped sway public opinion with mainland organizations, which was a game changer.On Sept. 11, 1964, Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Fire Island National Seashore Bill, establishing officially that the 33 miles of Fire Island be recognized as a National Park.However, Verga said that the fight was not over. In addressing sea level rising and threats to species on the island, he spoke of another kind of visionary – the late Irving Like of Dunewood, who championed the idea of a World Heritage Site designation.Under the jurisdiction of the United Nations, a world heritage site has to meet two of 10 selected criteria set by the World Heritage Convention. “Cherry Grove is one symbolic to human rights and the origins of the country’s gay rights movement,” Verga said in justifying criteria VI, which states: “be directly or tangibly associated with events or living traditions, with ideas, or with beliefs, with artistic and literary works of outstanding universal significance.” (The Committee considers that this criterion should preferably be used in conjunction with other criteria, according to the UNESCO website).Verga also draws upon the 300-year-old globally rare, below sea level Sunken Forest rich in American holly, sassafras, shadblow, black cherry and pitch pine trees as meeting criteria IX: “be outstanding examples representing significant and ongoing ecological and biological processes in the evolution and development of terrestrial, fresh water, coastal and marine ecosystems and communities of plants and animals.”The quest to save Fire Island remains ongoing.Christopher Verga is also author of “Civil Rights on Long Island,” co-authored “Bay Shore” with Neil Buffett, “World War II on Long Island: The Homefront in Nassau and Suffolk,” and the upcoming “Cold War Long Island,” co-authored with Karl Grossman (scheduled for release in October of 2021.)

Author of “Saving Fire Island from Robert Moses,” Christopher Verga, delivered a virtual lecture, hosted by Fire Island School Adult Education Program, on Thursday, July 15, giving those who tuned in a presentation about the fight for a national seashore.He spoke about Robert Moses’s decades long vision to create a four-lane highway cutting through the 17 individual communities and barrier beaches that establish Fire Island. Verga says this theoretical highway would have connected to Ocean Parkway, then run to Montauk Point, though Moses was not trained as an engineer, architect or urban planner.Verga dove into the beginnings and endings of Moses’s “master builder” career, and it was immediately clear that he is no fan of Robert Moses.“Moses’s projects gave little credence to environmental impacts,” Verga said. “Like closing inlets … now this is why we struggle with brown tide. If the inlets were open, high tide would naturally flush out the back bay. We’re still dealing with the ramifications of Robert Moses to this day.”Severe storms and flooding worried residents on and off the island, and Moses’s highway proposals were reconsidered as he claimed throughout the 1950s that they would anchor shifting and eroding dunes.The lecturer explained that first district Congressman Stuyvesant Wainright was the first to propose Fire Island be recognized as a national park. Moses labeled Wainwright an elitist, killing his national park proposal and his reelection.Verga said from this point in history, in a formula to activism, Dunewood’s own Maurice Barbash, home builder and environmental activist, was instrumental in blocking the project. “Barbash was inspired by landscapes and individualistic communities not dependent on cars,” Verga said.Barbash contacted every group that would benefit from the preservation of Fire Island, including the chamber of commerce, sports and fishing groups, and the ferry companies. He understood the importance of contacting elected officials and had artists create awareness posters. He also stressed the importance of withdrawing financial support from pro-highway candidates. This grassroots activism helped sway public opinion with mainland organizations, which was a game changer.On Sept. 11, 1964, Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Fire Island National Seashore Bill, establishing officially that the 33 miles of Fire Island be recognized as a National Park.However, Verga said that the fight was not over. In addressing sea level rising and threats to species on the island, he spoke of another kind of visionary – the late Irving Like of Dunewood, who championed the idea of a World Heritage Site designation.Under the jurisdiction of the United Nations, a world heritage site has to meet two of 10 selected criteria set by the World Heritage Convention. “Cherry Grove is one symbolic to human rights and the origins of the country’s gay rights movement,” Verga said in justifying criteria VI, which states: “be directly or tangibly associated with events or living traditions, with ideas, or with beliefs, with artistic and literary works of outstanding universal significance.” (The Committee considers that this criterion should preferably be used in conjunction with other criteria, according to the UNESCO website).Verga also draws upon the 300-year-old globally rare, below sea level Sunken Forest rich in American holly, sassafras, shadblow, black cherry and pitch pine trees as meeting criteria IX: “be outstanding examples representing significant and ongoing ecological and biological processes in the evolution and development of terrestrial, fresh water, coastal and marine ecosystems and communities of plants and animals.”The quest to save Fire Island remains ongoing.Christopher Verga is also author of “Civil Rights on Long Island,” co-authored “Bay Shore” with Neil Buffett, “World War II on Long Island: The Homefront in Nassau and Suffolk,” and the upcoming “Cold War Long Island,” co-authored with Karl Grossman (scheduled for release in October of 2021.)

Remembering the Story to Save Fire Island