A Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award Finalist Comes to Sayville

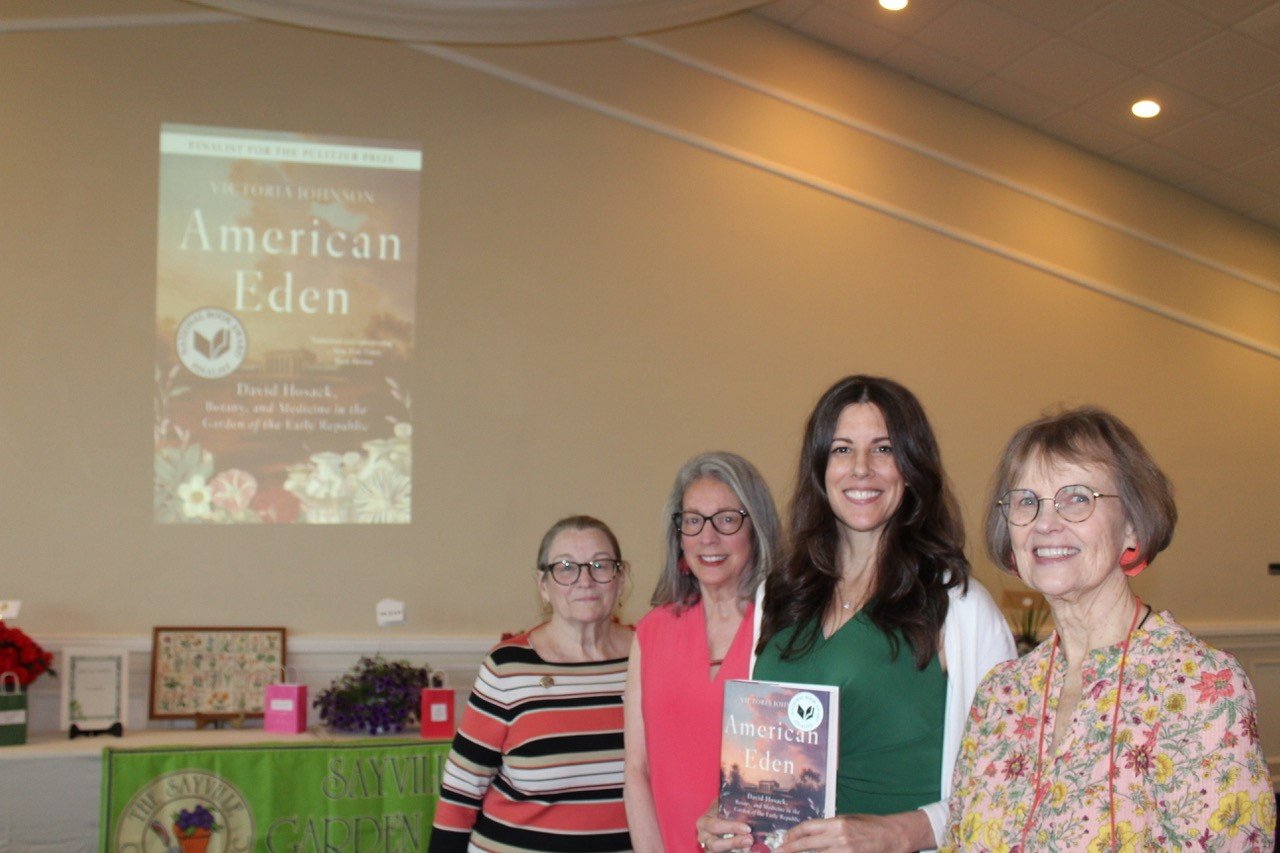

Photo: Author Victoria Johnson was the featured speaker at the recent Sayville Garden Club luncheon. Johnson, holding her book, is flanked by (left to right) Co-President Kate Rowe, Co-President Marge Ort, and First Vice President Gini Tucker.

It’s not every day you get a Pulitzer Prize finalist and a National Book Award for Non-Fiction finalist to speak at a garden club luncheon, but that’s what happened recently when the Sayville Garden Club hosted author Victoria Johnson, professor of Urban Policy and Planning at Hunter College, at Land’s End Restaurant.

Her book, “American Eden: David Hosack, Botany and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic,” chronicles the story of Hosack, who created the first 20-acre public botanical garden in the U.S., part of which is now under Rockefeller Center.

“I want to take you to Manhattan in 1797, a doctor, David Hosack, is rushing to administer to a 15-year-old boy at No. 26 Broadway, in the grip of a terrible fever,” she began. “He knew doctors had brought down fevers with cold cloths then, but he drew a steaming bath, and mixed in a botanical remedy called Peruvian bark, then several bottles of alcohol, lowered the boy’s body in, then added smelling salts. The boy’s pulse began to quicken. Hosack took him out of the bath, swaddled him with blankets and remained in a nearby room, dozing. When Hosack awoke, Alexander Hamilton was kneeling by his son’s bedside. He took Hosack’s hand in thanks for saving his son, Philip, and became a friend and advisor.”

That incident propelled Hosack towards his lifelong journey to create the nation’s first botanical garden. He persevered, steadily advancing towards his goal, in spite of ridicule, disappointments, and personal tragedies, never faltering.

Johnson riveted the crowd with Hosack’s story, an ardent doctor who first studied medicine and botany in Great Britain; in Edinburgh he discovered his passion, botany, and learned that most of the medicines of the time came from the plant world. But he didn’t know what specific plants cured illness. “He felt it was a matter of life and death for America’s future,” Johnson said. In London, he roamed the wilds and identified plants and dissected them. “After two years there, he was the best trained botanist in the U.S. He was 25.”

There’s a skill in writing a book like this, that takes you back to the time when our nation was young and was dealing with diseases that were wiping out families; he advocated for smallpox vaccinations early on. But also, that era was a rollicking one for party politics, indeed there were fears the country would fall apart, but also committed civic engagement. Although he became friends with and knew many of the heavy hitters of the day, like Thomas Jefferson, he stayed out of any partisan allegiances. Even after Hamilton’s death in the 1804 duel with Aaron Burr (he attended to him when he was gravely wounded and was devastated), Hosack remained friends with Burr. He believed a good doctor depended on neutrality.

In 1801, after purchasing 20 acres of land, he established The Elgin Botanic Garden. While Peruvian bark was effective, it was scarce and expensive, as were other medicinal plants. So he set out collecting thousands of species. “The Elgin Botanical Garden was created down a winding road surrounded by trees and plants. He built a spectacular structure, a 200-foot glass house flanked by hot houses,” Johnson said. “Between 1801 and 1811 he collected over 3,000 plants. He used the garden to conduct the first pharmaceutical research in the U.S. He became one of the most famous men of his time.”

There’s a lot more, but you’d have to read Johnson’s book. Trust us. It’s brilliant and fascinating.

Johnson said it took eight years to write, between teaching stints. Her research led her to local and far-off places. “I went to over 30 archival collections including the New York Historical Society, Library of Congress, New York Public Library archives, New York Academy of Medicine, New York Botanical Garden, and some archives in the United Kingdom, in London and Edinburgh. It’s the most fun I ever had, being on that trail where maybe I’ll find a piece of paper here, then something unexpected there. One thing was, I thought I’d tell the story of a botanical garden but what I discovered reading Hosack’s papers and those of friends of his, I was in awe how civic-minded they were and the foundations they established. I discovered he was part of this group of young people, women included, who had grown up looking to their elders and were possessed by this energy and shaping civic life so that it was stable and putting the U.S. on the new ground. The other thing entrancing was anything I found out about Manhattan Island, New Jersey and Long Island covered with plants and fields and thinking of that time when it was so alien to us now. Those people tramping through fields and collecting plants.”

Johnson’s epiphany about Hosack came when she read a book about the New York Botanical Garden, founded in 1891. “In this book, there were a couple of pages about this man who founded a much earlier botanical garden and I’d never heard about him. Then I read a sentence that that land is now Rockefeller Center. I thought it was such a cool New York story. I had to know about this.”

During the presentation, Johnson was asked what struck her the most about Hosack. “It was a perseverance with this vision to create these institutions (New York Historical Society, Museum of Natural History, first public schools and others) to help fellow Americans. It governed his every waking minute. He was endowed with brilliance, and he took this gift and put it into his city and nation. Without that type of person our civic life would be impoverished.”

Living with a subject for eight years, did she ever feel his presence? Johnson laughed. “I had such a strong connection with him. My sister, Jessica, a painter and musician, called him `your dead lover.’ I visited his grave and met descendants. There were two branches, both came who never met each other at my book party. They were so supportive of the book.”