Monarchs Part II

In the first half of this article about monarch butterflies we explored their appearance, biology and migration patterns. We closed by asking how is it possible for such a delicate creature to make such a huge trip from Mexico to Maine in the spring, and then back again in late summer?

The answer is, they don’t, yet they do! I’ll explain…

Although a monarch can fly an average of 30 miles per day and reach speeds up to six miles per hour, it still takes them four or five generations to make the trip all the way north. I find that astonishing, but at least it seems a little more proportionate to the size and longevity of the butterfly compared to the distance traveled.

But just as I was getting my head around the fact that each generation was traveling 700 or 800 miles in its short lifetime, I discovered that in the autumn each individual makes the entire 3,000 mile journey south, in a single generation!

Relative to body size, that’s like asking a human to walk around the earth several times! And yet somehow, they manage despite huge challenges from climate change, pollution, habitat loss and predation.

Captive-raised monarchs are also capable of migrating to overwintering sites in Mexico, but they have a lower success rate than wild monarchs.

Monarchs undergo complete metamorphosis; their life cycle has four phases: egg, larva, pupa, and adult. Monarchs transition from eggs to adults during warm summer temperatures in three to 10 weeks, depending on temperature. During their development, both larvae and their milkweed hosts are vulnerable to weather extremes, predators, parasites, and diseases.

The adult emerges from its chrysalis after about two weeks of pupation. The emergent adult hangs upside down for several hours while it pumps fluids and air into its wings, which expand, dry, and stiffen. The butterfly then extends and retracts its wings. Once conditions allow, it flies and feeds on a variety of nectar plants. During the breeding season, adults reach sexual maturity in just four to six days. However, the migrating generation does not reach maturity until overwintering is complete. Typically, fewer than 10% of monarch eggs survive to adulthood!

In both caterpillar and butterfly form, monarchs ward off predators with a bright display of contrasting colors to warn them of their undesirable taste and poisonous characteristics. They consume and synthesize chemicals (cardenolides) that interfere with cardiac functions in most predators.

Still, several species of birds have acquired methods that allow them to ingest monarchs without experiencing ill effects, including the black-backed oriole, black-headed grosbeak, brown thrashers, grackles, robins, cardinals, sparrows, and various jays. Additionally, some mice species are able to eat monarchs, as are Asian lady beetles (Harmonia axyridis) and the Chinese mantis (Tenodera sinensis). Predatory wasps also commonly consume monarch larvae. Automotive traffic is also a major threat, studies have shown that vehicles kill millions every year. But thankfully Fire Island has little of that, which is likely one reason the monarchs stop here!

Breeding monarchs prefer to lay eggs on swamp milkweed. But it’s an early successional plant that usually grows at the margins of wetlands and in seasonally flooded areas. The plant is slow to spread via seeds, does not spread by runners and tends to disappear as vegetative densities increase and habitats dry out. Although swamp milkweed can survive for up to 20 years, most live only two to five years in gardens. The species is not shade-tolerant and is not a good vegetative competitor.

In the northeastern United States, monarchs prefer to reproduce on common milkweed (A. syriaca), especially when its foliage is soft and fresh. Because monarch reproduction peaks during the late summer when milkweed foliage is old and tough, it should be mowed or cut back in August to assure that it will be regrowing rapidly when monarch reproduction reaches its peak.

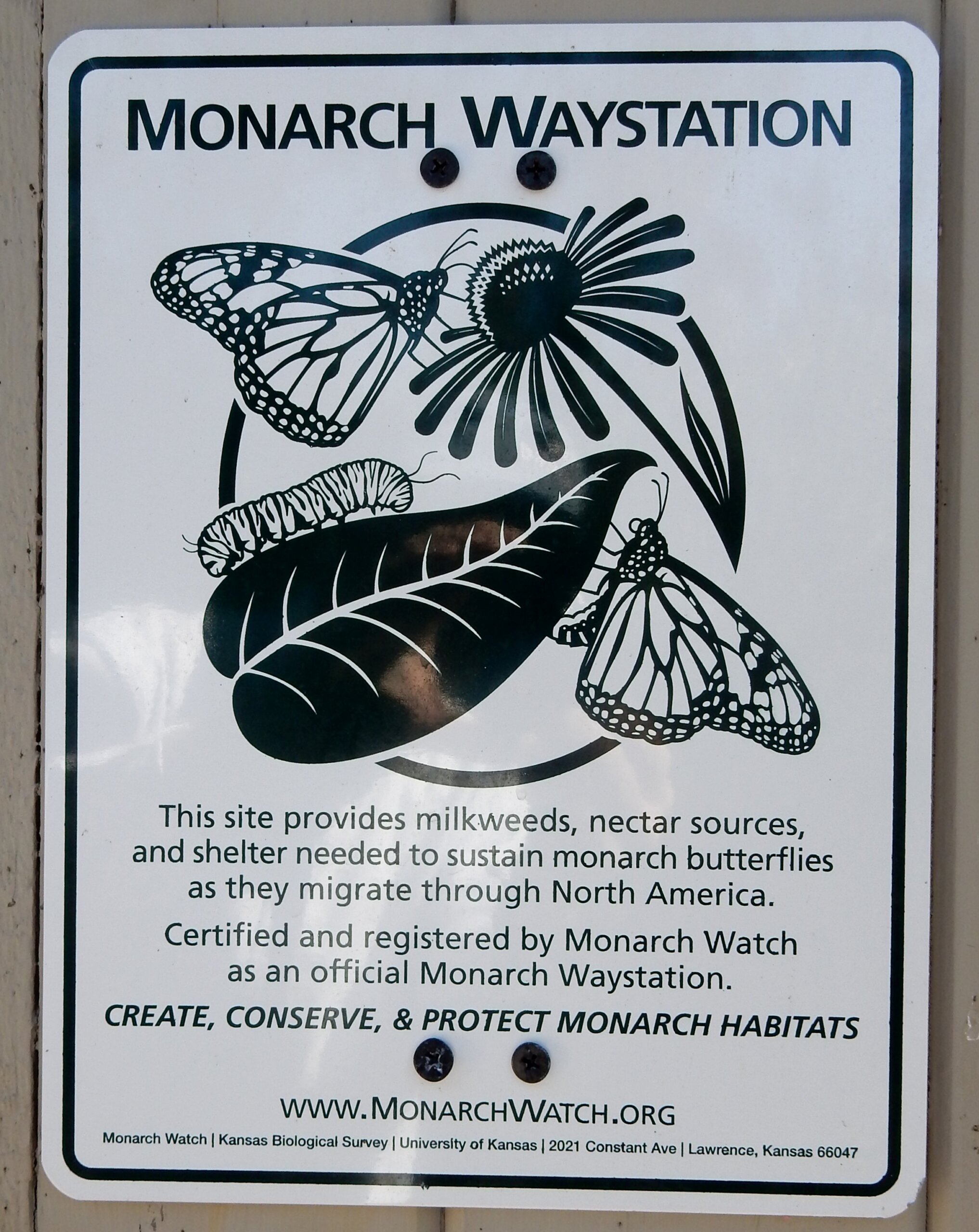

Organizations such as MonarchWatch.org encourage creating waystations (see picture) by planting the monarch’s primary host plant, Asclepias Milkweed, of which there are about three dozen species. You can visit their website for more information and to participate in various efforts to support and preserve the amazing monarch, one of the most beautiful insects to visit Fire Island!