The man who has experienced a shipwreck shudders at even a calm sea, Roman poet Ovid famously wrote two millennia ago. These days, the many shipwrecks off Fire Island’s coast are more of a curiosity, their survivors resting in peace with their trauma left to the history books, but three local wrecks recently made news long after being involuntary interred in their watery graves

In December, the U.S. Navy announced that it finally solved the century-old mystery of what sunk the “USS San Diego,” the only major American warship lost in World War I – which sunk in the Atlantic eight miles south of FI. In February, news broke that Saint James Brewery in Holbrook is brewing a beer using yeast recovered from bottles on the “SS Oregon,” a British steam ocean liner that sunk 18 miles south of FI in 1886. And in May, the U.S. Coast Guard sent divers to remove thousands of gallons of oil from the “SS Coimbra,” a British tanker that has been producing sheens decades after it sunk about 30 miles south of FI during World War II.

The San Diego, Oregon, and Coimbra are part of what scuba divers affectionately refer to as New York’s “wreck valley,” a 60-mile area that’s a veritable graveyard for hundreds of sunken ships resting at the ocean floor. Many fell victim to Fire Island’s infamously treacherous sand bars, but for these three, that was not the case.

San Diego Mystery

The USS San Diego

For a century, the reason why the San Diego sunk remained an unknown it took to its grave 110 feet underwater.

The 500-foot cruiser, having recently completed its mission of escorting ships across the North Atlantic to Europe, had fueled up in Rhode Island and its crew of more than 1,000 were hours from a night out in New York City when an explosion blew a hole in the hull on July 19, 1918. After 15 minutes, the captain ordered the crew to abandon ship as it capsized. It sunk in 28 minutes. Six crew members were lost. “The site serves as a stark reminder of how close enemy action came to the American coast during the war,” said Rear Admiral Samuel Cox, U.S. Navy (Ret.), director of Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC).

The three prevailing theories were that either a saboteur snuck aboard and planted a bomb, a German U-boat torpedoed it, or the ship hit a German mine. To get to the bottom of it, NHHC renewed the inquiry into the cause of the sinking for the WWI centennial. After a two-year investigation in which a team of historians, academics, and oceanographers collected data during six dives at the site, the NHHC announced on Dec. 11 that it believes the San Diego was sunk by one of two types of mines laid by German submarine U-156, an infamous vessel that patrolled the East Coast torpedoing ships and laying mines during the war.

“With this project we had an opportunity to set the story straight and by doing so, honor [the lost sailors’] memory and also validate the fact that the men on board did everything right in the lead up to the attack as well as in the response,” said Alexis Catsambis of the NHHC’s Underwater Archeology Branch, who led the probe. “The fact that we lost six men out of upwards of 1,100 is a testament to how well they responded to the attack.”

Cheers To Oregon

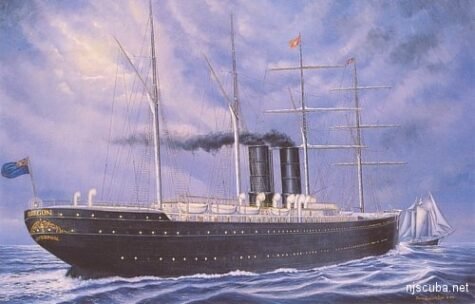

A painting depicting a schooner colliding with the “SS Oregon.”

The oldest of the news-making shipwreck trio – the only one of the three not lost in war – has the most uplifting story.

In February, news went viral of an upstate New York brewer making beer using yeast harvested from bottles that divers salvaged from a 133-yearold shipwreck. A week later, there was a twist: The owner of Saint James Brewery in Holbrook was about to release his own shipwreck suds pulled from the same ship. The first beer the LI brewery made from it was fittingly dubbed Deep Ascent. “One of the divers I had enlisted to help me find these bottles with the intent of making beer had given one of them to this other brewer, unbeknownst to me,” Jamie Adams of Saint James Brewery told The Associated Press.

The shipwreck in question was the “SS Oregon,” which rests in 125 feet of water. The Oregon, which broke records for its speed in its day, was on its way to New York from Liverpool, England, when it collided with a schooner at 4:30 a.m. on March 14, 1886. The Oregon initially stayed afloat, but the captain gave the order to abandon ship after two hours when attempts to plug the hole failed. All but one of the 852 passengers aboard survived, although all hands on the schooner are believed to have been lost.

As for the beer, Adams spoke to the upstate brewer and the two negotiated a deal to avoid stepping on one another’s toes.

The Coimbra Conundrum

The British tanker “SS Coimbra” is seen in this U.S. Coast Guard photo from 1941. (Courtesy U.S. Coast Guard)

The deadliest of the three wrecks is the oil tanker Coimbra, which was twice torpedoed by German submarine U-123 at 9:41 a.m. on Jan. 14, 1942, killing all but 10 of the crew of 46. The explosion was said to be so massive that it could be seen 30 miles away in the Hamptons.

The ship, which sunk in minutes and now rests in 150 of water, was believed to still have some oil within its tanks, but it was unknown how much of the 2 million gallons it was holding remained. But in 2009, when the East Hampton Star reported that a recreational diver came to the surface covered in oil after diving on the wreck, officials started taking a closer look. Satellite images indicated periodic sheens in the area. Recent assessments indicated that it’s leaking from a pinhole.

“With that small amount of seepage, it’s very easily weathered away or burned off by the sun,” U.S. Coast Guard Chief Warrant Officer Allyson Conroy told the Southampton Press, which reported in late May that divers recently removed about 70,000 gallons of oil from the ship.

All told, this marks the first time a Fire Island shipwreck has made news in seven years, when Superstorm Sandy further exposed the “Bessie White” wreck on the beach east of Davis Park. Since shipwrecks rarely make for good news – like in the case of an intentionally sunk ship to create an artificial reef hopefully it will be a while before any more make headlines.