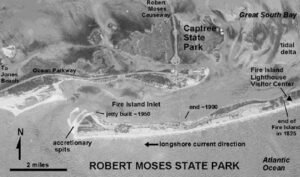

By Timothy Bolger Building a massive steel and concrete structure known as a flood gate that could temporarily close the mouth of the Fire Island Inlet may prevent hurricane storm surge from inundating the South Shore of Long Island, according to a new federal study stirring up debate.Flood gates could also be built in Jones Inlet, Rockaway Inlet, and a cross-bay barrier could be constructed along the Jones Beach Causeway to further mitigate storm surge from flowing from the Great South Bay into the western bays, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (ACE) officials say. The proposals are the subject of a preliminary report and two recent public hearings on what’s known as the Nassau County Back Bays Coastal Storm Risk Management Study – one of several big ideas getting scrutiny since Superstorm Sandy.“There’s significant environmental impact potentially associated with some of the solutions we’re proposing,” Scott Sanderson, a project manager for ACE told those gathered for a public hearing on the topic on June 12, at Freeport Village Hall. “To really understand the potential environmental mitigation costs that’s going to come with some of these projects, it’s going to take time and money.”As huge of an undertaking as the idea sounds, it’s still not the most ambitious one ACE is currently studying. Even more sprawling is the NY & NJ Harbor & Tributaries Focus Area Feasibility Study (HATS) that is studying the possibility of constructing even larger tide gates, including a 46-foot high steel barrier between Sandy Hook, New Jersey, and Breezy Point, Queens, to protect New York City from storm surge.“We assume that the surge gates would initially be operated for a two-year storm event, which would say once on average event two years, but as sea level rise occurs, that would increase,” said Bryce Wisemiller, an ACE project manager on the HATS study that is trying to “determine when and how they would be operated and for how long.”HATS, which is further along in its review than the back bays study, cautioned that such hard structures can cause flooding elsewhere.“The closure of the barriers appears to enhance ocean storm surge for most of the simulated events ‘outside’ of the closed barrier,” the authors of HATS wrote near the end of the 136-page interim report. “Potential for induced flooding outside of the closed barriers needs to be further analyzed in subsequent modeling efforts to better understand any induced impacts, as well as the potential to avoid and mitigate for those impacts.”Experts following the issue aired the same concern.

Building a massive steel and concrete structure known as a flood gate that could temporarily close the mouth of the Fire Island Inlet may prevent hurricane storm surge from inundating the South Shore of Long Island, according to a new federal study stirring up debate.Flood gates could also be built in Jones Inlet, Rockaway Inlet, and a cross-bay barrier could be constructed along the Jones Beach Causeway to further mitigate storm surge from flowing from the Great South Bay into the western bays, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (ACE) officials say. The proposals are the subject of a preliminary report and two recent public hearings on what’s known as the Nassau County Back Bays Coastal Storm Risk Management Study – one of several big ideas getting scrutiny since Superstorm Sandy.“There’s significant environmental impact potentially associated with some of the solutions we’re proposing,” Scott Sanderson, a project manager for ACE told those gathered for a public hearing on the topic on June 12, at Freeport Village Hall. “To really understand the potential environmental mitigation costs that’s going to come with some of these projects, it’s going to take time and money.”As huge of an undertaking as the idea sounds, it’s still not the most ambitious one ACE is currently studying. Even more sprawling is the NY & NJ Harbor & Tributaries Focus Area Feasibility Study (HATS) that is studying the possibility of constructing even larger tide gates, including a 46-foot high steel barrier between Sandy Hook, New Jersey, and Breezy Point, Queens, to protect New York City from storm surge.“We assume that the surge gates would initially be operated for a two-year storm event, which would say once on average event two years, but as sea level rise occurs, that would increase,” said Bryce Wisemiller, an ACE project manager on the HATS study that is trying to “determine when and how they would be operated and for how long.”HATS, which is further along in its review than the back bays study, cautioned that such hard structures can cause flooding elsewhere.“The closure of the barriers appears to enhance ocean storm surge for most of the simulated events ‘outside’ of the closed barrier,” the authors of HATS wrote near the end of the 136-page interim report. “Potential for induced flooding outside of the closed barriers needs to be further analyzed in subsequent modeling efforts to better understand any induced impacts, as well as the potential to avoid and mitigate for those impacts.”Experts following the issue aired the same concern. “If you’re stopped the water from going someplace, it’s got to go somewhere else,” Aram Terchunian, a coastal geologist who’s president of Westhampton Beach-based First Coastal Consulting Corp., told Newsday. “The question is how much and where? Until they do some real hard modeling, they’re not going to know the answers.”That is to say, how the problem applies to the back bays and Fire Island remains to be seen, as the 74-page inlet flood gate study has yet to delve into the issue. The back bay report’s managers have requested an extension to continue conducting the feasibility study beyond September, when the threeyear mandate to complete it expires. If the extension is granted, ACE officials expect to have a recommendation on which approach to the idea they prefer that can be released for public review by next year, but a final report, funding appropriations, and construction are years, if not decades away – assuming the study gets completed and any of its eventual recommendations get approval.Fire Islanders are of course familiar with the process, having witnessed the glacial pace of the Fire Island Inlet to Montauk Point Reformulation Study (FIMP) initiated more than a half century ago and which only got funding after the $50 billion Sandy aid package passed following that storm causing $65 billion in damage in 2012. Of course, the FIMP project deals more with rebuilding dunes on the barrier islands and raising roads on LI’s South Shore. It doesn’t include sea walls or tide gates that raise concerns about tidal flow, pollution, and boat navigation.Freeport Village Mayor Robert Kennedy, a proponent of the the flood gates who had been lobbying for the back bays study and toured a hurricane protection barrier in New Bedford, Massachusetts, last year in his push, was eager for a quicker solution before the next major storm strikes.He asked the ACE officials at the meeting, “Are you going to start working on the gates next week?” The question sparked the only laughter in the 90-minute meeting, where the dozens of attendees were familiar with the slow speed of such mind-numbingly complex government projects.As any FIMP follower knows, anybody holding their breath waiting for construction crews to show up at Democrat Point will likely sooner see the pearly gates than construction of inlet flood gates.

“If you’re stopped the water from going someplace, it’s got to go somewhere else,” Aram Terchunian, a coastal geologist who’s president of Westhampton Beach-based First Coastal Consulting Corp., told Newsday. “The question is how much and where? Until they do some real hard modeling, they’re not going to know the answers.”That is to say, how the problem applies to the back bays and Fire Island remains to be seen, as the 74-page inlet flood gate study has yet to delve into the issue. The back bay report’s managers have requested an extension to continue conducting the feasibility study beyond September, when the threeyear mandate to complete it expires. If the extension is granted, ACE officials expect to have a recommendation on which approach to the idea they prefer that can be released for public review by next year, but a final report, funding appropriations, and construction are years, if not decades away – assuming the study gets completed and any of its eventual recommendations get approval.Fire Islanders are of course familiar with the process, having witnessed the glacial pace of the Fire Island Inlet to Montauk Point Reformulation Study (FIMP) initiated more than a half century ago and which only got funding after the $50 billion Sandy aid package passed following that storm causing $65 billion in damage in 2012. Of course, the FIMP project deals more with rebuilding dunes on the barrier islands and raising roads on LI’s South Shore. It doesn’t include sea walls or tide gates that raise concerns about tidal flow, pollution, and boat navigation.Freeport Village Mayor Robert Kennedy, a proponent of the the flood gates who had been lobbying for the back bays study and toured a hurricane protection barrier in New Bedford, Massachusetts, last year in his push, was eager for a quicker solution before the next major storm strikes.He asked the ACE officials at the meeting, “Are you going to start working on the gates next week?” The question sparked the only laughter in the 90-minute meeting, where the dozens of attendees were familiar with the slow speed of such mind-numbingly complex government projects.As any FIMP follower knows, anybody holding their breath waiting for construction crews to show up at Democrat Point will likely sooner see the pearly gates than construction of inlet flood gates.