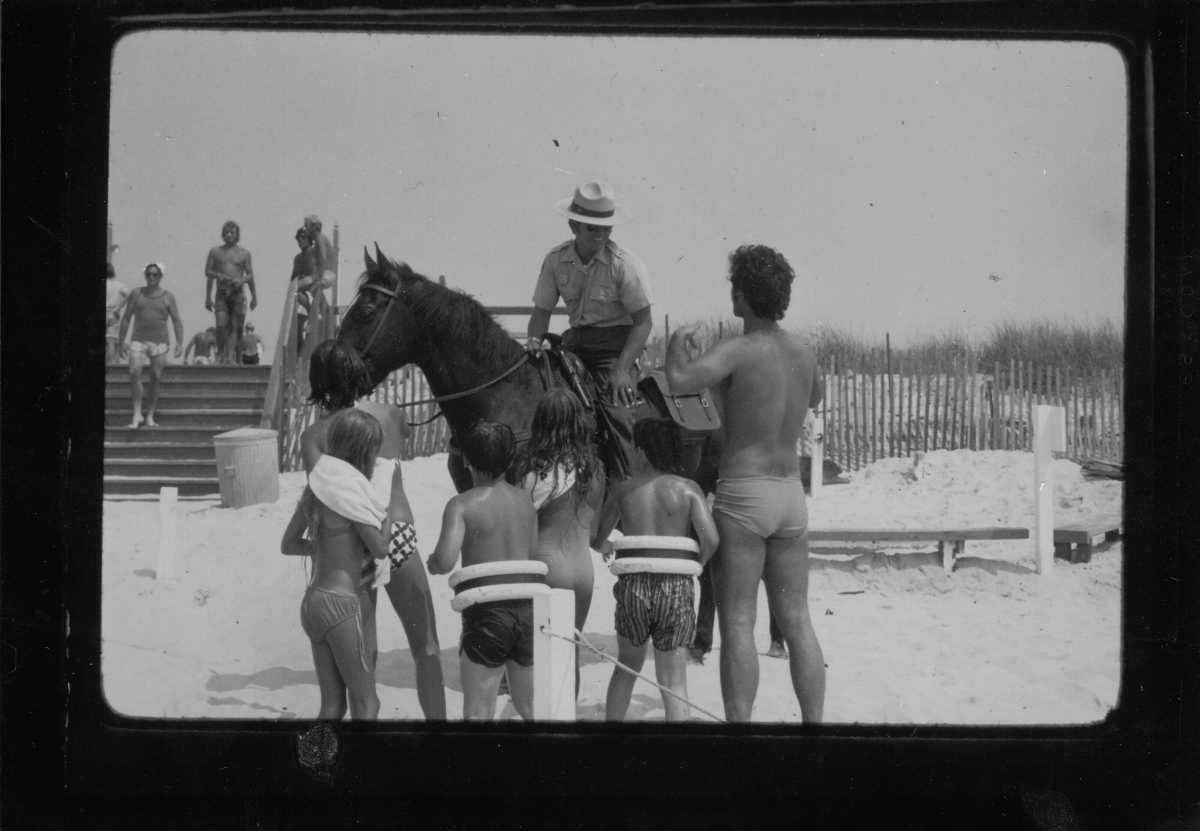

I was a seasonal Ranger stationed at Watch Hill with the new Fire Island National Seashore (FINS). One August, I was assigned to be the horse ranger for the rest of the summer. A Horse ranger? I grew up in Queens!

I had never ridden a horse before, but the federal government spared no expense to train me. They gave me a two-hour class at a woman’s family farm in East Patchogue. She had me riding a gentle horse named Sundown.

The next day, I rode Bandit, a sturdy Morgan horse who had retired recently from the NYC Police Department. He lived in a stable just east of the Watch Hill campground. I quickly found out that Bandit was the one in charge. He was especially fond of fresh, tender poison ivy leaves, which grew in the swale behind the dunes. I tried to be nonchalant as summer bathers expressed surprise at seeing a ranger and horse atop the dunes marked with “Keep Off Dunes” signs.

Sometimes, Bandit enjoyed wading a little too deep in the surf. On those occasions, my riding boots were filled with water until I got better at coaxing him back to dry sand. I’m sure these spectacles provided entertainment for the campers and beachgoers. However, they also gave me a week of painful saddle sores and a fair amount of sunburn.

I didn’t have a regular patrol schedule. The horse was more or less a goodwill ambassador to make people feel better about the federal government’s takeover of Fire Island. To many of them, the Park Service represented the enemy.

I rode on the trail behind the primary dunes known as “Burma Road.” Burma Road cuts through bayberry, beach plum, catbrier, and beach roses as it follows the natural swale between primary and secondary dunes.

It promised to be another hot day as I passed the dune cut in front of Skunk Hollow. Several beach cottages were scattered, and I saw a few people on the beach. They were naked and waved as I went by. This was not a surprise. Skunk Hollow was an unofficial nudist beach. The Seashore’s position on this was to ignore it.

A few hundred yards along the trail, I spooked a white-tailed deer with a couple of fawns. Deer were less common in those days. The little family quickly faded into the scrub pine and high-bush blueberry north of the trail. Red-winged blackbirds chirred liquid notes from the thicket. Over the marsh, a harrier hawk cruised low for rodents or rabbits.

Bandit was a star wherever we went.

I hadn’t gone a hundred yards before I passed the beach house of John and Sarah Ince. Both Ince’s were waiting by the front door with carrots for Bandit. Like everyone living in the wilderness area, they knew that they were living on borrowed time. In the late 1960s, FINS had given all the residents a temporary lease. These ranged anywhere from 5 to 25 years. Sarah and John still had a dozen or so years left, and they were determined to enjoy every day of it. Their little house was filled with bird carvings, old bottles, and assorted treasures from the beach. The front door was propped open with part of a rib from the “Bessie White,” a coasting schooner that went aground on the beach in 1922.

Continuing my patrol, I rode through the most desolate part of the wilderness area. There were no squatter shacks in the two-mile stretch to Old Inlet. A set of fox prints in the sand were the only signs of life. The dunes here were massive. Some soared 30 feet above the low tide line. Many were streaked with the deep purple tint of fine garnet sand and topped with billowing beach grass. It was a unique wilderness of sand, sky, and vegetation, enclosed by ocean and bay.

There were a few signs of civilizations past. The rusted-out frame of a Model-A Ford lay off the trail; its skeletal remains were almost hidden in the catbrier and poison ivy. Some old timbers emerged from the sand. Perhaps remnants of a ship that sank in the inlet more than a century earlier.

Old Inlet was a navigable inlet in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Fishing boats and coasting schooners regularly accessed the ocean and bay through its shifting channel. During the Revolutionary War, a pair of British warships used it to anchor in the bay near the Manor of St. George. However, it was a dangerous inlet even then. In 1821, it claimed the “Savannah,” the first ship to use steam power to cross the Atlantic. By the 1840s, the inlet had shrunk to a mere trickle after a series of storms and shipwrecks that blocked the channel.

As I rode Bandit along the hot swale enclosed by high dunes, I hadn’t a clue that the island would be breached by a new inlet years later.

Monarch butterflies flutter purposefully, heading west at the beginning of their southern migration. Nothing is forever. Let’s hope everyone will always have a vision of Old Inlet and her sister communities. All of them are gone now, consigned to the history of Fire Island.