1942 Rolf Tietgens/(C) Diogenes Archives

Cherry Grove in the mid-1950s was a community of founding families and new homeowners. Also, absentee landlords or landladies who rented to a mix of mainland friends, and increasingly to the visible ‘Greenwich Village set’ (homosexuals). Same-sex attracted renters were majority male, but a small, vibrant group of ‘women who love women’ also found a safe harbor there.

Audrey Hartmann with her partner Maggie MacCorkle (1924-2005) adopted Cherry Grove’s affinity community. Maggie appeared in the Arts Project’s revues of the 1950s. Audrey refugeed from Ocean Beach. They shared a cottage with a group of men. Hartmann described mid-1950s Grove women as older, quiet, and very attractive. No more than 15 or 20 women arriving by train, limousines, seaplanes, and Criss-Crafts. Well-educated, smart, a lot of them rich. Maggie and Audrey met and mingled with Rizzoli executive Natalia Danesi Murray and New Yorker’s Janet Flanner (lovers), APCG’s Margot Johnson and Kay Guinness (a couple), and Young and Rubicam’s graphic artist, Mary Ronin, among others.

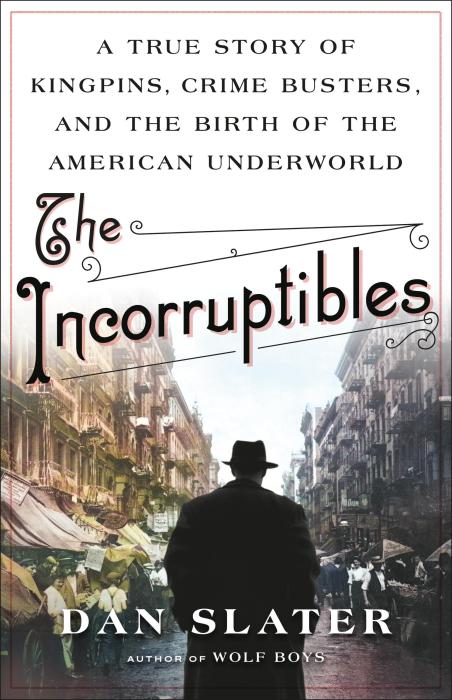

It was also an arriviste’s paradise. “Strangers on a Train,” a first novel and Alfred Hitchcock’s 1951 film adaptation, catapulted author Patricia Highsmith (1921-1995) into newfound wealth and celebrity status. She became a frequent visitor to Cherry Grove.

Highsmith was also a deeply conflicted lesbian (with an occasional male fling). In “Diaries and Notebooks: 1941-1995” she describes murder as “a kind of making love” or “possession,” and contemplates “making murder entertaining.” She confesses murderous impulses toward a woman “who almost made me love her.” In one diary entry, Pat sunbathes in Cherry Grove to avoid attending to her ex-lover, Ellen Hill, who attempted suicide. The suicide is woven into the plot of Highsmith’s “The Blunderer.” This kind of cognitive dissonance informs the motivations of Highsmith’s often charming but very disturbing fictional characters – creatures of her alternate persona.

Lesbian networks flourished in Cherry Grove. The connections often, though not always, originated with ‘a little interlude’ between friends. Highsmith visits Cherry Grove courtesy of Natalia Danesi Murray and Margot Johnson. Johnson, Highsmith’s literary agent, appeared as a ‘butch’ Berenice, and Mary Ronin as a lamé-gowned ‘tomboy’ Frankie Addams in “Dismembering the Wedding.” It was the Arts Project’s 1950 camp parody of Carson McCullers’ novel and stage play “The Member of the Wedding.” Highsmith wooed and had one of those ‘ little interludes’ with Mary Ronin in the late 1950s. Highsmith was smitten. Ronin was in a relationship and otherwise unavailable. This pattern of attraction is emblematic of Highsmith’s personal relationships and also of her fascinating, psychologically complex, fictional characters. Highsmith credits the Ronin triste as a contributing influence to her psychological thriller, “This Sweet Sickness” (New York 1960).

Highsmith’s “Diaries” describes Mary Ronin (1912-1992) as possessing contradictory personality traits; “naive” and “wise,” as well as “generous” and “selfish.” Such dualities often combine as character traits creating the duplicitous natures of Highsmith’s murderous characters like “The Talented Mr. Ripley,” or David Kelsey of “This Sweet Sickness.” Kelsey literally adopts dual identities in pursuit of his unattainable love, Annabelle (Ronin’s doppelganger.) The most interesting parallel is Highsmith’s alter ego Kelsey’s obsession with Annabelle. It maps so closely the particulars of Pat’s pursuit of Ronin. The alternate reality playacted by Kelsey under his assumed identity, William Neumeister, is writer Highsmith’s fantasy love life with Mary Ronin put to paper. Mary and Pat go their separate ways. David Kelsey comes to a disastrous end.

“Mary Ronin is another world to me…I love her…because she changes everything but my past.” Highsmith’s future was changed repeatedly by Margot Johnson’s savvy editorial advice. She contributed to a landmark in queer literature. “The Price of Salt” (1952) by “Claire Morgan” (Patricia Highsmith’s pseudonym) originally had the two lovers, Therese Belivet and Carol Aird break up. The heroines’ storyline is based on Highsmith’s actual lived events as a sales clerk in Bloomingdale’s toy department one Christmas season.

Johnson persuaded Highsmith to give the lovers a happy ending. Before this, lesbian storylines ended in bitterness, death, or insanity of the protagonists. “Diaries” reveal another lived event, and a familiar trope in Highsmith’s novels, involving Johnson’s lover Kay Guinness. “A brief and delightful” interlude, so characteristic of both Pat and Kay. Highsmith decides cannily to “end this infatuation” fearing a “destructive aftermath between Margot and Kay” once Pat departs Cherry Grove.

Highsmith published “Salt” under her own name in 1991. It was made into the 2016 film “Carol” starring Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara. Happy ending? To be with Therese, Carol leaves her husband and must give up her children. So, there’s that. Patricia Highsmith – talented, perhaps troubled – but unmistakably one of Cherry Grove’s own.