On Saturday, May 28, The William Floyd Estate in Mastic Beach, which has been a part of the Fire Island National Seashore since 1965, offered Long Islanders the opportunity to learn a more complex and all-encompassing history of the American patriot William Floyd. The program, Reframing the Past, aimed to incorporate perspectives that traditionally “go untold” in the history of Long Island.

National Parks Ranger Julie Flores led the program and from the onset she shared her enthusiasm to have the attendees “hear more of a dynamic history.”

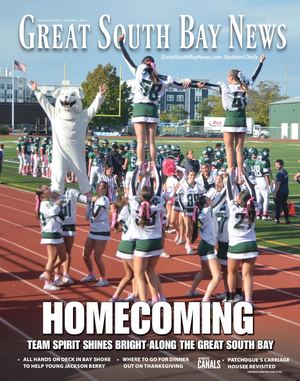

National Parks Ranger Julie Flores in front of the Old Mastic House at the William Floyd Estate in Mastic Beach.

Following a brief walk through the wooded acreage of the grounds, the boardwalk led to the Old Mastic House, the main building of the estate. William Floyd’s grandfather, Richard Floyd, came to the colonies from Wales in the 1600s. The Old Mastic House was built in 1724 and operated as a plantation. This is the house that William Floyd grew up in and inherited in 1755.

The tour stopped outside of the house and participants were given a general history of William Floyd. As one of the young children participating noted, there are many things around Long Island that are named after William Floyd. So, what made him so special?

Flores informed the program attendees of Floyd’s triumphs and accomplishments throughout his life. Tragically, Floyd had lost both of his parents to typhoid by the time he was 20 years old. He was left to run a plantation and raise his six younger siblings. While maintaining the family estate, Floyd still managed to get involved in other activities, such as local politics.

Flores shared that Floyd was often described as having an “innately inquisitive mind.” He was oftentimes captivated by revolutionary ideas and causes. In fact, Floyd was elected to the First and Second Continental Congresses. He continued his involvement in politics following the American Revolution and up until the year 1791. But perhaps most notably of all, William Floyd is one of only four New Yorkers to have signed the Declaration of Independence, and he is the only resident of what we now know as Suffolk County to have a signature on the historic document.

Following this overview of Floyd’s life, Flores invited participants to think about history as a story. They were then able to understand how different perspectives can work to reframe a story. Flores used the example of Cinderella, a character recognizable and beloved by many. She invited them to contemplate how various characters, from the mice to the evil stepmother, would talk about Cinderella.

How do we feel about Cinderella after hearing all these perspectives? Another young participant seemed to get it right: We have mixed emotions. It’s not all good or all bad, it’s complicated.

From this point, the program shifted to focus on the perspective and experience of historically underrepresented people.

As was already addressed in the initial story, the Floyd’s were plantation owners. Flores was able to offer a fuller picture of this lifestyle by including the fact that the Floyd family “cultivated this property with the labor of enslaved black people, indentured servants and members of the indigenous Unkechaug tribe.”

It was at this point that Flores presented an old receipt outlining Floyd’s purchase of “a boy named Phillip” on July 28, 1758.

In all, there were 14 slaves on the Floyd plantation. Flores noted that this information about slavery in the northern colonies is oftentimes shocking. However, she also shared that “New York enslaved more people than the New England colonies combined.” And of that number, more than half lived on Long Island.

It is because this knowledge is not well-known that programs such as Reframing the Past work to tell the stories of those whose voices were lost through the years.

There were other documents that were shared with program participants, such as more receipts for servants and slaves, a census of the enslaved across the area, and a sort of contract between William Smith and the Unkechaug leaders ensuring that the land of the indigenous tribe would not be seized without their consent. The latter promise did not end up protecting the tribe from “very one-sided land transactions” in the years that followed, as evidenced by the size and location of the Floyd estate.

The tour concluded at the family cemetery. It was at this location that Flores spoke a bit more about the significance of perspective and physical historical evidence. She explained that due to their lack of privilege or wealth, “we do not have any resources that come directly from the underrepresented.”

But that doesn’t mean that we can forget those groups either because if we only look at the perspective of the Floyd family “we get a skewed view.”

So, as Flores says, we must use the historical evidence we can gather “to create a different narrative.”

That process comes with flaws, as there will be some things that we will never know for certain. For example, Flores presented an invoice for the medical care of one of the Floyd’s enslaved servants from January of 1765, and presented various motives for Floyd’s actions here: “Out of goodwill or protecting his investment?”

Without more equality in which perspectives are retold throughout history, we can never know the full story. But the Reframing the Past program and Park Ranger Julie Flores are here to remind us that it is always important, and never too late, to be “enlightened on underrepresented voices.”