Editing the Supremes… Everyone edits communications. We edit our thoughts before we speak or, regrettably, sometimes not. Informal writing, hopefully, gets a casual or careful review before sending it to friends. More care is exercised in our word choices for business or scholarly writing.

When it comes to ‘word works’ to be published, an editor takes over the wordsmith’s product. Single-author creations can cover wide swaths of subject matter. Their purpose is to inform, persuade, or entertain. Sometimes all three.

Technical and professional publications, for instance, on legal subjects, require the author’s expertise and that of the editor. Legal documents are subject to meticulous editing for accuracy. A court’s written opinion settles a case and can create new law for others to reference.

What many authors share in common is a sense that their words are inviolate. The editor’s job is to support this viewpoint while tactfully correcting errors that slip into even the best technical writing. Imagine an editor’s challenge when nine individuals opine on a single topic and submit their words for official publication. Words that can change the law of the United States for generations to come.

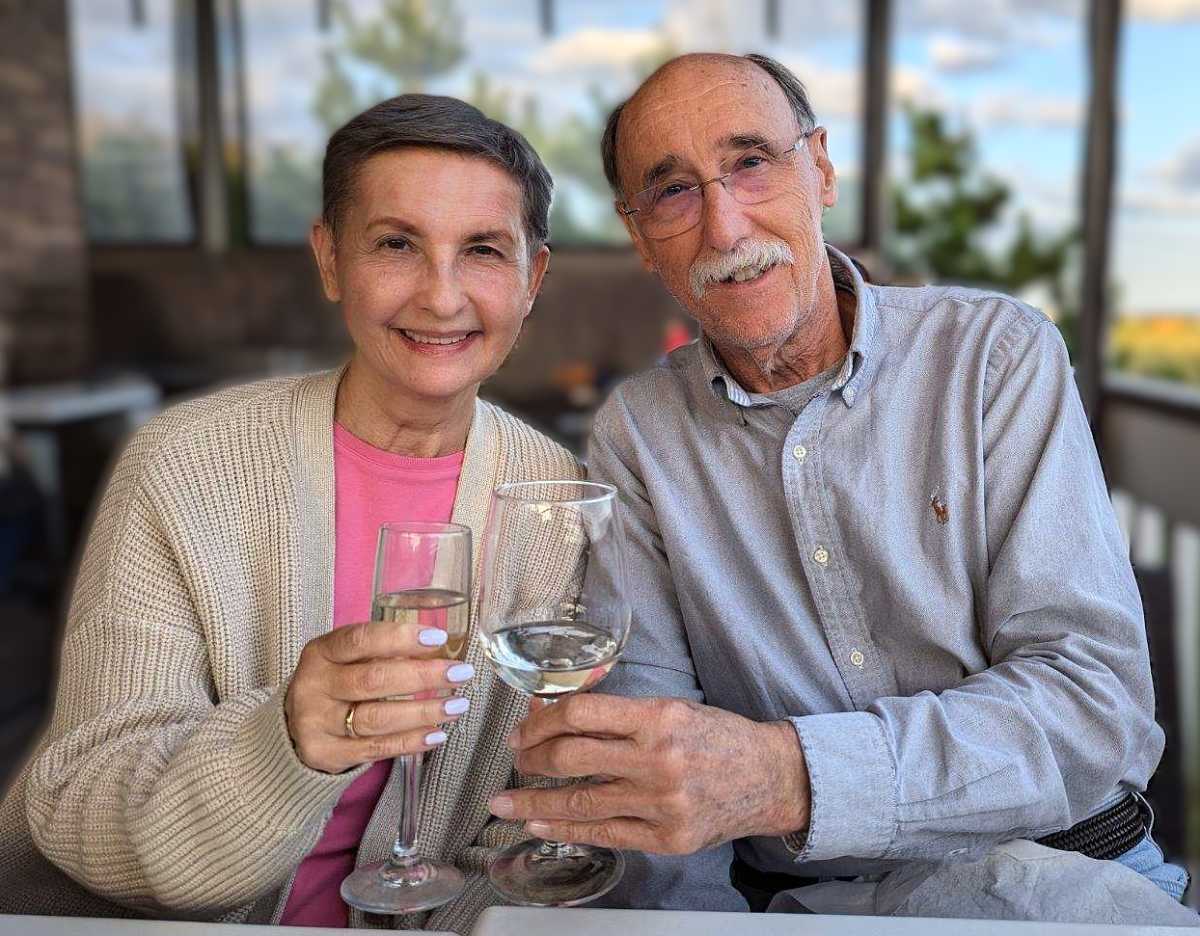

Meet Christine Luchok Fallon, appointed in 2011 as the first female Reporter of Decisions of the United States Supreme Court. Christine, now retired, is enjoying an August vacation and a Wedding Anniversary with family at the Fallon cottage in Cherry Grove. She was responsible for technical edits, syllabus production, and analytic summaries of SCOTUS opinions during her 31-year tenure as the Deputy Reporter and then Reporter.

In editing a SCOTUS decision, words are indeed sacrosanct. The Reporter of Decisions doesn’t alter, delete, or amend the substance of an opinion. Christine’s job, and her deputies, was proofreading for technical precision: citations, typographical errors, etc. Before a decision gets to the Reporter, four Justices must decide to hear a case.

Over 7,000 lower court rulings are submitted annually to the Supreme Court for review. The Justice’s clerks read and recommend cases for hearing. Christine trained new law clerks, including now Justices Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, Amy Coney Barrett, and Ketanji Brown Jackson, on Reporter’s office procedure. Parties to selected cases submit briefs; the reasons each thinks they are right. “Friends of the Court” briefs may be filed. Each is reviewed. First opinions are formed.

The oral arguments phase is the only part of this process made public. Parties to the case present their position summary. The Justices ask questions to clarify legal points being argued. The nine Justices subsequently meet and vote to decide the cases argued that week. They are the only people in the room. Five Justices can determine a case’s outcome. If the Chief Justice is in the majority, he decides who will write the majority opinion. If he’s not, then the senior Justice in the majority assigns the task. A draft opinion is then written and circulated.

Christine recounted when draft opinions were circulated on paper, and then the introduction of computerization.

“An opinion now circulates by email to the Justices’ chambers, the law clerks, and the Reporter’s office. It can go back and forth among the editors and Justices until the Justices decide that the opinion is ready for release. For some opinions, it’ll be a week and then they’re done. But others may take months. It’s a very formal procedure. A Justice who wants to join an opinion or write a side opinion, like a dissent, sends an email with a memorandum or joins a memorandum already attached. Before an opinion is released to the public, the Reporter or her Deputy writes a syllabus,” an outline that lays out the facts of the case and the reasoning for its decision.

Christine is a Constitutional scholar in her own right. In response to a question about disagreements among the judges, Christine answered:“The court is a very collegial place. That’s just not made up.”

Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia were good friends.

“The Justices can disagree intellectually without being disagreeable. They are very respectful of each other. I didn’t always agree with their decisions, but they didn’t always agree with each other either, as when Justice Kennedy authored Obergefell” (2015 gay marriage decision). I remember reading those opinions and the part where Kennedy notes how things have changed and how society views gay people now. They are our neighbors. Their children go to school with ours. And it’s true because you can see the difference here (in Cherry Grove) when I first came in the 70s and how it is now.”

A full circle from the days Christine’s father-in-law, James V. Fallon, Sr., would post bail, defend, and his juries acquit gay men arrested for “outraging public decency” in 1950s Cherry Grove.