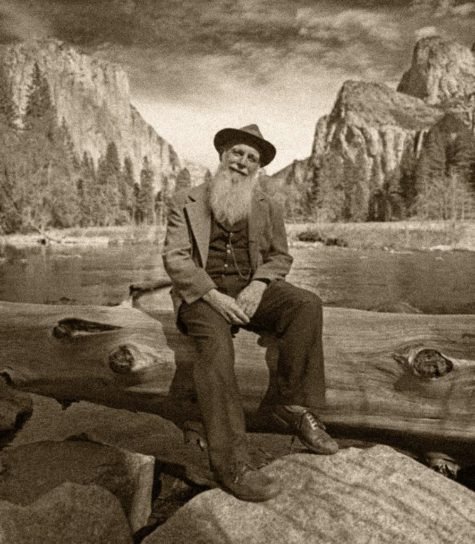

IT IS ONLY FITTING that as we celebrate the 100th anniversary of the founding of our National Park System on Aug. 25, 2016, we should also celebrate the life of John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club and the man rightfully called the “Father of the National Parks.”John Muir (April 21, 1838 – December 24, 1914) is a well-known hero among environmentalists, but for those unfamiliar with his story here is a brief summary.John Muir was born in Dunbar, Scotland, and immigrated to Wisconsin, U.S. with his family at the age of 11. John had a curious, inventive mind and at the age of 22 he had devised several practical devices that he presented at the local state fair in Madison, devices that won prizes. Among his inventions were a horse feeder, a thermometer, and a gadget that tipped him out of bed in the morning.John’s father allowed him to get up at 1 a.m. to study if he desired, to which John rhapsodized: “I had gained fi?ve hour?s, almost half a day!?? ?Fiv?e hou?rs to m?yself?! F?ive huge, solid hou?rs?!? can har?dly? think? of any other event of my life, any discovery I ever made that gave birth to joy so transportingly glorious as the possession of these fi?ve f?rosty? hour?s.”?? And study he did, his main interests being botany and geology, subjects he pursued his entire life.“The mountains are calling me and I must go.”In 1867 he suffered an eye injury that blinded him for about a month. Upon recovery he vowed to spend the rest of his days surrounded by nature and thus began his wander?lust? ??his affl?iction has d?riv?en me to the sweet fields. ?God has to nea?rly? k?ill us sometimes, to teach us lessons.”He walked 1,000 miles from Indianapolis to Cedar ?Key?, ?Flo?ida, ?”by? the wildest, leafiest and least tr?odden way I could.” He caught a boat to Cuba, Panama, and, eventually, San Francisco. There he asked for the best way out of town. “Where do you want to go?” he was asked. “To any place that is wild,” he replied.And so it was that he found himself wading through waist high wild ?flowers in the ?San ?Joaq?uin Valley, into the high country of the Sierra Nevada M?ountains.? ?He wr?ote? ???”From this v?ast golden ?flower? bed rose the mighty Sierra, miles in height, and so gloriously colored and so radiant, it seemed not clothed with light, but wholly composed of it, like the wall of some celestial city…the Sierra should be called the Range of Light.” He found Yosemite. He found home.“In every walk with nature one receives more than he seeks.”Muir remained in the Sierra Nevada’s for several years working as a shepherd, a guide and running a sawmill. His intimate exposure to the wilderness convinced him that Yosemite Valley had been formed by glacie?rs and not by? ea?rth?quak?es as was the popular? notion of the time. This brought him to the attention of many scholars, including one of his favorite authors, Ralph Waldo Emerson, who knocked on his log cabin door and tried to induce Muir to go east and become a teacher. Muir, however, considered himself an ongoing student of nature and remained in the mountains, ea?rning the sobr?i?quet ??”John of the ?Mountains??.”

“How terribly downright must be the utterances of storms and earthquakes to those accustomed to the soft hypocrisies of society.”Now and again he would leave the valley. He lived in San Francisco for a time writing a series of articles, entitled Studies in the Sierra, which launched his literary career. He would go on to write over 300 articles and 10 books. He continued traveling and made his fi?rst t?rip to ?Alask?a in 1880. ????? ?Upon r?etu?rning from Alaska, he married Louie Wanda Strentzel, and they would raise two daughters together. He went in partnership with his father-in-law for 10 years, managing their fruit farm with great success.His wife encouraged his travels and he took several more trips to Alaska, as well as South America, Australia, and even to the Far East. He would take his daughters on his “local” trips whenever possible. He once told a visitor to his farm, “This is a good place to be housed in during stormy weather…to write in, and to raise children in, but it is not my home. Up there,” he said, pointing towards the Sierra Nevada, “is my home.” The house and part of the farm are now designated as the John Muir National Historic Site.“These temple destroyers, devotees of ravaging commercialism, seem to have a perfect contempt for Nature…lift their eyes to the Almighty Dollar.”

Yosemite Valley was being threatened by “hoofed locusts,” the derogatory name Muir had coined for sheep. Muir was alarmed by the perceived danger of losing this pristine wilderness forever.He fell in with Robert Underwood Johnson, editor? of ?Century?? ?Magaz?ine, one of the most infl?uential publications of its time. They were both of a mind to save Yosemite and a series of articles, written by Muir and published by Johnson, brought much needed attention to the problem. In 1890 Congress created Yosemite National Park. Muir was also personally involved in the establishment of the Grand Canyon, G?lacier?, ?Se?quoia, and ?Mount ?Rainier? ?National ?Pa??rks earning him the well-deserved title of “Father of the National Parks.”Encouraged by Johnson, Muir went on to found The Sierra Club in 1892, based on the model of the Appalachian Mountain Club. He became its president and served as such until his death in 1914. The club?s fi?rst maj?or? battle was the damming of ?Hetch Hetchy Valley to provide water for San Francisco. A debate between the preservationists and the conservationists ensued.?The ?Sie??rra ?Club e?ventually? lost that fight, but the debate aroused public interest in the preservation of these wilderness areas and led to the creation of the National Park Service on Aug. 25, 1916.“A fast and a storm and a difficult canon were just the medicine I needed.”John Muir was strong and sinewy, 5-foot, 9-inches tall and never weighed more than 150 pounds. He traveled light. “I rolled up some bread and tea in a pair of blankets with some sugar and a tin cup and set off…” usually with a copy of Emerson.On his many adventures he oftentimes had little concern for his personal safety. He loved storms and would venture out so that he could enjoy their fury and grandeur.“When I heard the storm and looked out I made haste to ?oin it? fo? man? of ?atu?e?s finest lessons are to be found in her storms.”On one occasion he clung to the face of a precipice with no hope of reaching its top only to, somehow, do so. He purposely climbed to the top of a 100-foot spruce in the middle of storm so that he could watch the wind. In Alaska he left camp with a dog that was named Skiteen in the middle of a blizzard just to go exploring. He was gone for some 16 hours, at one point forced to bridge a glacial crevasse on a narrow sliver of ice. Somehow or other he survived all these travails – and others.“No amount of word-making will ever make a single soul to ‘know’ these mountains. One day’s exposure to mountains is better than a cartload of books.”

While Muir is well known for these many exploits, he is little known for the facility of his writing – prose that approaches poetry. Take this example of his description of a storm on Mount Shasta:About half past 1 o’clock P.M. thin fib?rous cloud films began to blow directly over the summit of the cone from north to south, drawn out in long fairy webs, like carded wool, forming and dissolving as if by magic. The wind twisted them into ringlets and whirled them in a succession of graceful convolutions, like the outside sprays of Yosemite falls; then sailing out in the pure azure over the precipitous brink of the cone, they were drifted together in light gray rolls, like foam wreaths on a river.And take this description of his view from the top of that 100-foot spruce he climbed in the middle of a storm:There is always something deeply exciting, not only in the sounds of winds in the woods, which exert more or? less infl?uence ov?er? ev?ery?? mind, but in their? ?va?ried water?lik?e ?flow as manifested by the movements of the trees, especially those of the conifers. By no other trees are they rendered so extensively and impressively visible, not even by the lordly tropic palms or tree ferns responsive to the gentlest breeze. The waving of a forest of the giant Sequoias is indescribably impressive and sublime, but the pines seem to me the best interpreters of winds. They are mighty waving goldenrods, ever in tune, singing and writing wind-music all their long century lives. Little, however, of this noble tree-waving and tree-music will you see or hear in the strictly alpine portion of the forests.

John Muir died of pneumonia in Los Angeles at the age of 76 during a brief visit with his daughter. He was survived by his two daughters and 10 grandchildren.Scotland, the land of his birth, commemorates his birthday with John Muir Day. They have also named a 130-mile route John Muir Way in his honor.The Muir Woods National Monument, Muir Beach, John Muir College, Mount Muir and Muir Glacier are all named in his remembrance, and still the list continues on: He has a butterfly, ??a pi?ka, a millipede, a w?ren, two species of aster, a rose, and even a mineral – all named after him.

H?e might find fault, howev?er?, with one name in particular – the 211-mile John Muir Hiking Trail in the Sierra ?Nev?ada ?Mountains.? ?He would find no fault in the trail itself, which he would love, but in its name.“Hiking –” he wrote, “I don’t like either the word or the thing. People ought to saunter in the woods – not hike! Do you know the origin of that word ‘saunter?’ It’s a beautiful word. Away back in the Middle Ages people used to go on pilgrimages to the Holy Land, and when people in the villages through which they passed asked where they were going, they would reply, ‘a la sainte terre,’ to the Holy Land. And so they became known as sainte-terre-ers or saunterers. Now these mountains are our Holy Land, we ought to saunter through them reverently, not ‘hike’ through them.”God bless you John Muir.