Book Review: “The World Broke in Two”

By Rita Plush

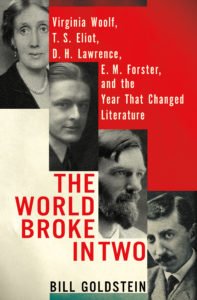

“The World Broke in Two: Virginia Woolf, T. S. Eliot, D. H. Lawrence, E. M. Forster and the Year That Changed Literature”

Bill Goldstein

Henry Holt & Company

$30 Literary Criticism

Virginia Woolf, T.S. Eliot, D.H. Lawrence, and E.M. Forster are literary heavyweights, but not too heavy for Bill Goldstein to weigh in on in their featured role in “The World Broke in Two.” A narrative account of their work and lives during the birth of literary modernism, the title derives from author and literary critic Willa Cather’s comment that writing styles changed so drastically “in 1922 or thereabouts,” as to cause a systemic break in the world of books.

Goldstein, founder of The New York Times books’ website and recipient of numerous writing fellowships, attributes Cather’s “break” to the horrors of World War I and a collapse in the beliefs of the established order. Betrayed by the war and the “unprecedented scale of killing,” the aforementioned authors and others of their ilk rejected their governments and regimes. Abandoning accepted notions of plot, setting and character, they strove to find original ways of self-expression and interpreting the world. Or, as Goldstein so gracefully puts it, they struggled to “confront and pin down on paper the texture and vitality of a new landscape of the mind.” Their concepts were open-ended and personal; time was not fixed, but supple and adaptable, the writers traveling from present to past and back again. Stream of consciousness as a viable means of moment-by-moment thinking established itself as a narrative style.

A case in point, Goldstein notes James Joyce’s “Ulysses.” Hailed as one of the most important works of modernist literature and published in 1922, the event prompted Ezra Pound to exclaim that it “marked the end of the Christian era.” As if there was a new God, this reviewer posits, and one’s spiritual life would never be the same.

Folks who have never read a book of literary analysis should not be put off by thinking “The World Broke in Two” is hard to digest theory and academic minutiae. It is nothing of the kind. It is an easy-going-down, fascinating peek into the lives of four great 20th century writers who changed the way we look at and read literature.

Goldstein puts his writers in full focus with their times and each other, their elegant prose often set against their inelegant lives. Woolf (“Mrs. Dalloway”) suffered health problems and the influenza that was sweeping England in the 1900s. Elliot (“The Wasteland”) had a nervous breakdown while caring for his chronically ill wife. Forster (“A Passage to India”) was a homosexual, and virgin till he was 37. He never enjoyed a relationship that was at the same time emotionally and physically satisfying, all the while grappling to “invent the language of the future.”

Goldstein’s formidable research includes the diaries of these modernist masters, comments from critics and friends, their notes and letters and love affairs gone bad, plus his own careful understanding of the their works, offering the reader an in-depth study of how these fearless writers carved great books from their great minds and offered them to an often hostile public.

Lawrence’s “Lady Chatterley’s Lover,” originally published in private editions, labeled him a “pornographer” for its explicit and frank depiction of sex between a couple belonging to different classes. Lawrence himself was personally controversial. “Childlike in the extreme, moody and given to tantrums,” there seemed “very little about Lawrence that wasn’t irritating to someone,” including his publisher who found him “‘ill-bred and hysterical.’” As opposed to Eliot who was liked “or even loved,” but not trusted because he dealt in a “very narrow, very selective truth.”

Admiring and envying their peers, they gossiped about each other, sent them drafts and chapters and worried about money – for Lawrence there was never enough – and finding publishers. Yes. Even the greats had trouble getting into print. Before and after her 40th birthday, Woolf, plagued with self-doubt, lamented that her career wasn’t where she thought it would be. Beset by depressions, she drowned herself with rocks in her pockets at age 59.

Both a mind and an eye-opener, “The World Broke in Two” explores the mutual respect and admiration these classic authors had for each other, their petty jealousies and offenses – which were many – and what makes a great book great. Readers heading for their libraries and iPads to check out or download a tome or two, will find Goldstein’s insights giving them a new understanding of why these masters have been read and reread for close to 100 years.

Virginia Woolf was wrong when she commented while reading Proust, “Well – what remains to be written after him.” Clearly, there was quite a bit.