The house on Bayberry where he stayed was originally purchased by his second wife, Katherine Tupper Brown in 1928. His first visit was in 1930 at the invitation of Katherine so he could meet her three children, Allen, Clifton, and Molly. While the younger two children had no problem with the invitation, Allen, then 12, told his mother, “I don’t know about that, we are happy enough as we are.” By next morning he had changed his mind and sent Marshall a letter in which he wrote: “I hope you will come to Fire Island. Don’t be nervous, it is OK with me.” He signed it, “A friend in need is a friend indeed. Allen Brown.” The visit went well and Marshall and Katherine were married that October.Marshall visited Katherine and the children as often as possible, but given the demands of his duties the visits were sporadic and usually brief. In a letter to General John J. Pershing in 1935 he wrote: “Molly [his step-daughter] had landed from her ten-month trip around the world, on June 5, and had opened the cottage. Allen came up from the University of Virginia at the same time. He ‘life guards’ at thirty bucks a week. Has made 10 rescues in the heavy surf.” This is the same Allen who originally challenged Marshall as an addition to their family.In an unhappy twist of fate, Allen Tupper Brown was shot and killed by a sniper on May 29, 1944. He was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star.After the hurricane of 1938, on Sept.26 in another letter to General Pershing, Marshall wrote of the harrowing experiences his wife encountered during that hurricane. “I returned to Washington Wednesday afternoon, and Thursday morning learnt of the terrific hurricane in the Northeast. The Western Union people told me I could not hope to communicate with Bay Shore, L.I., the point from which one takes a boat for Fire Island, where Mrs. Marshall has her cottage, for at least 24 hours; and as nothing was known of what had occurred on Fire Island, I took a plane and flew up to see what had occurred. From the air, I saw the cottage had not been destroyed, though most of the houses in the vicinity had collapsed or been demolished. Many on the bay side of the island — which is about 600 yards wide — had floated out in the water. On the ocean side, the dunes had been broken through by heavy seas and most of the cottages in that vicinity were destroyed. I flew over to Mitchel Field and procured a small training plane, and succeeded in landing on the beach. I found Mrs. Marshall and Molly all right, but they had had a terrific night and escaped from the cottage in water up to their waists, and in a 50-90 mile an hour gale. My orderly was with them and he did his part nobly. The next morning they took stock and found that the cottage had not been harmed, though destruction elsewhere had been terrific, and quite a few lives were lost. The adjacent community of Saltaire was completely destroyed, except for 6 cottages. I remained on the island and got Mrs. Marshall over to the Long Island side. On Friday evening I took her and Molly in to New York, where they now are, apparently none the worse for their experience.”This is the same hurricane, sometimes called The Long Island Express, that killed 600 people and caused over $4 billion in damages.Cameron Dunbar, a resident of Ocean Beach, recalled his encounters with the General. “When I was about ten years old, General Marshall came to Ocean Beach in an Army amphibian plane to visit [Katherine]. When the plane came in near the beach on the bay side, the tide was too low, and, therefore, they couldn’t get close enough to the shore to disembark. I saw them, rowed out to the plane, and then backed the rowboat against it. General Marshall hopped on, and I rowed him to shore. He gave me a tip. General Marshall only came to visit three or four times each summer, but after that day he would always circle Ocean Beach each time he came to visit and I would come from wherever I was to meet him in the rowboat.”In 1939 President Franklin D. Roosevelt promoted Marshall to Army chief of staff, in which capacity in just three years he transformed a rag-tag, ill-equipped Army of less than 200,000 men into a formidable fighting force of over 8 million soldiers. This feat was instrumental in the defeat of the Axis forces in WWII. He was promoted to a four-star general the same day Hitler invaded Poland triggering the war.The Army built a secret passage with a trap door in the house in which Marshall spent his time on Fire Island just in case either the Germans or Japanese came for him. Yet as much as he enjoyed his retreats to the island they eventually came to exasperate him. With the war fully engaged, in a letter dated May 14, 1941 he wrote: “I had good luck on the weather this trip, but a little bad luck otherwise. We were simply pestered to death by people coming in to talk over ‘the situation.’ A perfect stranger got into the house Saturday night and stayed for 2 hours. We went down town for dinner Saturday and I practically did not get to eat, as someone seemed always standing beside the table — being very pleasant and gracious but making it pretty difficult to get any relaxation. Fire Island has always been free of this sort of thing, so I was disappointed.”Marshall, “almost six feet tall, ramrod-straight, invariably proper, impeccably controlled, and determinedly soft-spoken,” had hoped to become the supreme allied commander in Europe, but President Franklin D. Roosevelt would not part with him due to his superior planning and diplomatic skills. “I could not sleep nights, George,” FDR told him, “if you were out of Washington.” The supreme allied commander title went to Dwight D. Eisenhower instead.But he was by no means overlooked for his accomplishments. Time magazine named Marshall their Man of the Year in 1943 and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill praised him as the “organizer of the Allied victory.” In 1944 he was made a five-star general, the first in history.

Wally Pickard, one of five generations of Pickards who have called Fire Island home for decades, became General Marshall’s aide. He joined the Army Air Corps and had been sent to Hickham Field in Hawaii to await further orders. The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor the following morning and Pickard was severely wounded.

Wally’s mother, not having heard from her son for two days, became concerned and asked Katherine Marshall to please see what she could discover. Katherine asked the general who took immediate action. Wally was shipped to Walter Reed Hospital in D.C. He had almost lost his hand, but a specialist was able to save it. Marshall, who Wally said was “a kind man but aloof,” took a special interest in Wally and assigned him as his aide, serving in adjacent offices at the Pentagon. Ever the optimist, Wally credits his wounds with exposing him to that “great experience that few men would ever have, something I can be proud of,” and, not incidentally, with saving his life. In a taped interview Wally ruminated: “Had I not been wounded in Pearl Harbor I would not have been fortunate enough to be talking to you [Richard Hein, the interviewer]. Could have been worse. I just know I’m lucky. And here I am talking to you. June 22, 2008, a beautiful day on Fire Island. Oh yeah, said it was going to rain. Sure doesn’t look like rain.”It is rumored that Wally holds the record for the most consecutive summers on Fire Island. He was brought over by his parents before his first birthday and returned every year, including the war years, until his death at the age of 93.With the war behind him, George Marshall resigned his commission in 1945 to become President Truman’s special diplomatic envoy and in 1947 he accepted appointment as secretary of state. In this capacity he drew up plans for aiding Europe’s recovery from WWII.Millions had died in the war. European industries had been all but destroyed, its infrastructure lay in ruins. Famine loomed. On June 5, 1947 at Harvard University’s commencement, Marshall delivered a 10-minute speech outlining the European Recovery Program. Many in government wanted to call this the Truman Plan but the president insisted that it be called The Marshall Plan. In 1947 Time magazine, once again, selected Marshall as their Man of the Year.Marshall retired in 1951. He and Katherine sold their home in Ocean Beach and moved to Dedona Manor in Leesburg, Virginia, about which he said, “this is Home…a real home after 41 years of wandering.” The house, now known as the Marshall House, is a National Historic Landmark and a museum.In 1953 George C. Marshall won the Nobel Peace Prize for The Marshall Plan. He is the only military officer to ever win this prize and about which he said in his Nobel acceptance speech: “There has been considerable comment over the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to a soldier. I am afraid this does not seem as remarkable to me as it quite evidently appears to others. I know a great deal of the horrors and tragedies of war. Today, as chairman of the American Battle Monuments Commission, it is my duty to supervise the construction and maintenance of military cemeteries in many countries overseas, particularly in Western Europe. The cost of war in human lives is constantly spread before me, written neatly in many ledgers whose columns are gravestones. I am deeply moved to find some means or method of avoiding another calamity of war. Almost daily I hear from the wives, or mothers, or families of the fallen. The tragedy of the aftermath is almost constantly before me.”George C. Marshall died in 1959 at the age of 78, and is interred at Arlington National Cemetery.We can be proud that a man of such accomplishments chose to wrest from his tumultuous life whatever leisure he could here on the sands of Fire Island.This article was originally prepared to commemorate the 70th Anniversary of General George Marshall’s famous speech delivered at Harvard University on June 5, 1947. This speech is often credited to opening the gateway to the program known as The Marshall Plan. Updated on May 24, 2020.

outlining the European Recovery Program. Many in government wanted to call this the Truman Plan but the president insisted that it be called The Marshall Plan. In 1947 Time magazine, once again, selected Marshall as their Man of the Year.Marshall retired in 1951. He and Katherine sold their home in Ocean Beach and moved to Dedona Manor in Leesburg, Virginia, about which he said, “this is Home…a real home after 41 years of wandering.” The house, now known as the Marshall House, is a National Historic Landmark and a museum.In 1953 George C. Marshall won the Nobel Peace Prize for The Marshall Plan. He is the only military officer to ever win this prize and about which he said in his Nobel acceptance speech: “There has been considerable comment over the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to a soldier. I am afraid this does not seem as remarkable to me as it quite evidently appears to others. I know a great deal of the horrors and tragedies of war. Today, as chairman of the American Battle Monuments Commission, it is my duty to supervise the construction and maintenance of military cemeteries in many countries overseas, particularly in Western Europe. The cost of war in human lives is constantly spread before me, written neatly in many ledgers whose columns are gravestones. I am deeply moved to find some means or method of avoiding another calamity of war. Almost daily I hear from the wives, or mothers, or families of the fallen. The tragedy of the aftermath is almost constantly before me.”George C. Marshall died in 1959 at the age of 78, and is interred at Arlington National Cemetery.We can be proud that a man of such accomplishments chose to wrest from his tumultuous life whatever leisure he could here on the sands of Fire Island.This article was originally prepared to commemorate the 70th Anniversary of General George Marshall’s famous speech delivered at Harvard University on June 5, 1947. This speech is often credited to opening the gateway to the program known as The Marshall Plan. Updated on May 24, 2020.

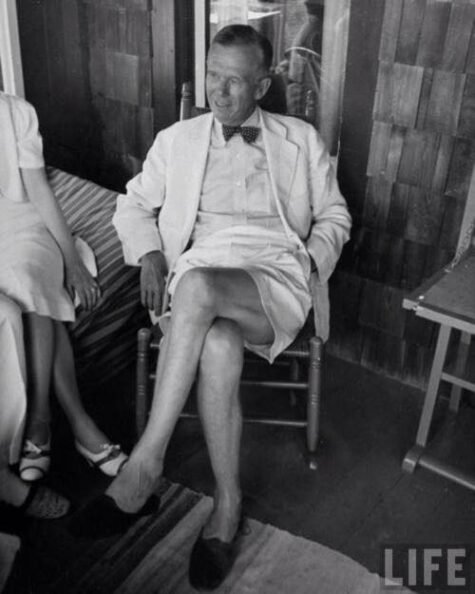

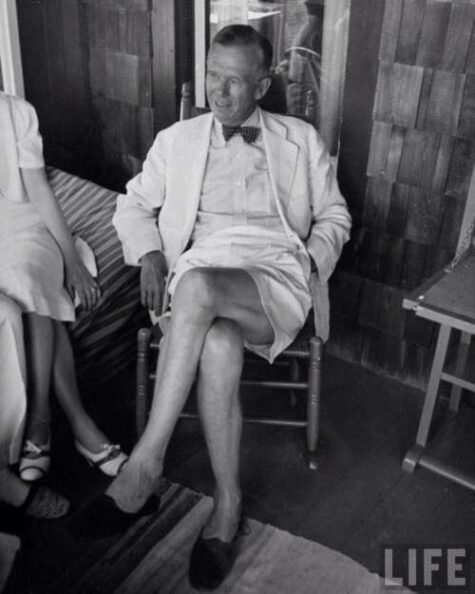

General George C. Marshall (Dec. 31, 1880 – Oct. 16, 1959) author of the internationally acclaimed and hugely successful Marshall Plan and recipient of the 1953 Nobel Peace Prize was a resident of Ocean Beach, Fire Island for over 20 years, from the summer of 1930 until 1951.

General George C. Marshall (Dec. 31, 1880 – Oct. 16, 1959) author of the internationally acclaimed and hugely successful Marshall Plan and recipient of the 1953 Nobel Peace Prize was a resident of Ocean Beach, Fire Island for over 20 years, from the summer of 1930 until 1951. outlining the European Recovery Program. Many in government wanted to call this the Truman Plan but the president insisted that it be called The Marshall Plan. In 1947 Time magazine, once again, selected Marshall as their Man of the Year.Marshall retired in 1951. He and Katherine sold their home in Ocean Beach and moved to Dedona Manor in Leesburg, Virginia, about which he said, “this is Home…a real home after 41 years of wandering.” The house, now known as the Marshall House, is a National Historic Landmark and a museum.In 1953 George C. Marshall won the Nobel Peace Prize for The Marshall Plan. He is the only military officer to ever win this prize and about which he said in his Nobel acceptance speech: “There has been considerable comment over the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to a soldier. I am afraid this does not seem as remarkable to me as it quite evidently appears to others. I know a great deal of the horrors and tragedies of war. Today, as chairman of the American Battle Monuments Commission, it is my duty to supervise the construction and maintenance of military cemeteries in many countries overseas, particularly in Western Europe. The cost of war in human lives is constantly spread before me, written neatly in many ledgers whose columns are gravestones. I am deeply moved to find some means or method of avoiding another calamity of war. Almost daily I hear from the wives, or mothers, or families of the fallen. The tragedy of the aftermath is almost constantly before me.”George C. Marshall died in 1959 at the age of 78, and is interred at Arlington National Cemetery.We can be proud that a man of such accomplishments chose to wrest from his tumultuous life whatever leisure he could here on the sands of Fire Island.This article was originally prepared to commemorate the 70th Anniversary of General George Marshall’s famous speech delivered at Harvard University on June 5, 1947. This speech is often credited to opening the gateway to the program known as The Marshall Plan. Updated on May 24, 2020.

outlining the European Recovery Program. Many in government wanted to call this the Truman Plan but the president insisted that it be called The Marshall Plan. In 1947 Time magazine, once again, selected Marshall as their Man of the Year.Marshall retired in 1951. He and Katherine sold their home in Ocean Beach and moved to Dedona Manor in Leesburg, Virginia, about which he said, “this is Home…a real home after 41 years of wandering.” The house, now known as the Marshall House, is a National Historic Landmark and a museum.In 1953 George C. Marshall won the Nobel Peace Prize for The Marshall Plan. He is the only military officer to ever win this prize and about which he said in his Nobel acceptance speech: “There has been considerable comment over the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to a soldier. I am afraid this does not seem as remarkable to me as it quite evidently appears to others. I know a great deal of the horrors and tragedies of war. Today, as chairman of the American Battle Monuments Commission, it is my duty to supervise the construction and maintenance of military cemeteries in many countries overseas, particularly in Western Europe. The cost of war in human lives is constantly spread before me, written neatly in many ledgers whose columns are gravestones. I am deeply moved to find some means or method of avoiding another calamity of war. Almost daily I hear from the wives, or mothers, or families of the fallen. The tragedy of the aftermath is almost constantly before me.”George C. Marshall died in 1959 at the age of 78, and is interred at Arlington National Cemetery.We can be proud that a man of such accomplishments chose to wrest from his tumultuous life whatever leisure he could here on the sands of Fire Island.This article was originally prepared to commemorate the 70th Anniversary of General George Marshall’s famous speech delivered at Harvard University on June 5, 1947. This speech is often credited to opening the gateway to the program known as The Marshall Plan. Updated on May 24, 2020.