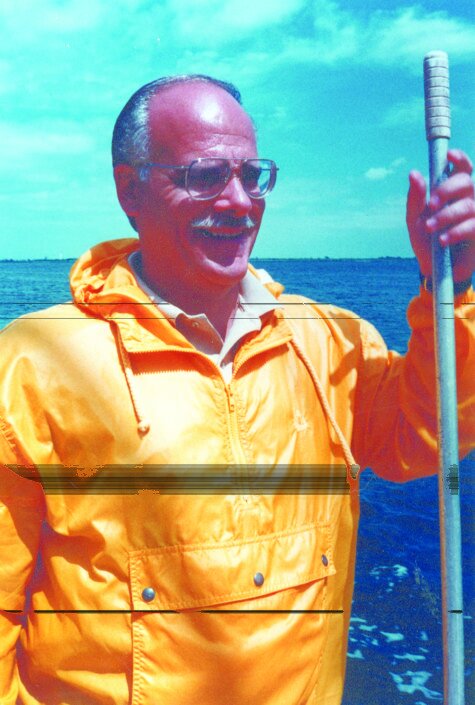

By Shoshanna McCollumIN CERTAIN CIRCLES, Dr. John Tanacrdi has earned the moniker of “The Horseshoe Crab Guy.” Anything you ever wanted to know about horseshoe crabs, this was the man to ask. For over 12 years he was the Chairman of Dowling College’s Earth Marine Sciences Department, which earned the college notable prestige over the last decade. Now a professor at Molly College, he is also the director of their Center for Environmental Research and Coastal Monitoring. (CERCOM) However our chat with him made it clear this is a man knowledgeable about many things – in addition to horseshoe crabs!

FIN: For many years I knew you as “the horse- shoe crab guy” at Dowling College, but now with you at Molloy it seems you have branched out into other things. Can you tell me a little about that?Tanacredi: The transition was not exactly a planned thing. Dowling is in a very difficult situation. Basically I was there for 13 years. In 2013 the president of Molloy College, who is a biologist, came by to see one of our shared lectures. I wasn’t necessarily looking to leave, but everything seemed to come into place, and it was really a saving grace. Molloy has fully supported us. I brought all my staff, I’m a full professor with the department, and I teach several courses: ecology and marine biology. At Molloy, they had a Bachelor of Science Degree for many years, in Urban Environmental Sciences. But Molloy also has a very big nursing program. We have over 2,600 nursing students, and they all have to take biology. Molloy is now being prepared for a Masters Degree in Coastal Environmental Management, which is presently pending in Albany. If approved we will be the only college in NYS to offer such a degree. I consider myself very fortunate.

FIN: I understand you had a very full career before entering academia. Can you tell me a little about that please?Tanacredi: For 24 years I was a coastal research supervisory ecologist with the National Park Service. I was stationed at Gateway [National Recreation Area] but I worked at all the coastal parks. I was detailed up to University of Rhode Island, at the Graduate School of Oceanography in Narragansett. It’s been a relatively simple and straight- forward career of environmental sciences, but I’ve had some unique experiences. I was a hurricane hunter with the U.S. Navy. I also worked with the U.S. Coast Guard for three years on Governor’s Island as a bridge administrator, preparing Environmental Impact Statements for bridge and highway construction for six states. That was an amazing experience. For three years I traveled in the Coast Guard Third District between Maine and Delaware, studying transportation infrastructure along bridges, waterways, and estuaries. It was truly an eye opening experience.

FIN: Are you still involved with the study of horse- shoe crabs at Fire Island?Tanacredi: The College has undergone a little bit of a Renaissance in trying to emphasize its Sustainability Institute, and CERCOM, which is the center at the old Blue Point Oyster Hatchery in West Sayville. It was an opportunity to promote the creation of a field station at Molloy. The field station does everything from captive breeding and aquiculture of horseshoe crabs, to studying and monitoring them. We have a program called the “Crab Club” where high school students get 1,000 eggs, and the school raises and then returns them to us at the end of the school year. We have a re-nesting pro- gram, and they go back where they came from out into the Great South Bay. The purpose of this is to increase the awareness of horseshoe crabs and protecting habitat, so that’s a big part of our program.

FIN: I understand a newly discovered species of crustacean was named after you. How did that come about?Tanacredi: When I was with the NPS, I worked with the Chilean National Park Service and was involved with world heritage designations through our international office in Washington D.C. The NPS sponsored three expeditions to Easter Island in 1998, 1999, and 2000. The book I wrote with my colleague John Loret, “Easter Island: Scientific Exploration into the World’s Environmental Problems in Microcosm,” was one result of those expeditions. As an invertebrates ecologist I worked with the Museum of National History and we collected over 4,000 specimens of animals that live in the “wave zones.” Easter Island has a very rough shoreline. So we brought the specimens back to the United States where they were divided up among scientists for further study. A crustacean specialist noted that one arthropod had not been identified as a known species. So in recognition of the National Park Service sponsorship, it was recommended that it be named after me, Cryptopontius tanacredii. It was a distinct honor, but it doesn’t look like me at all.

FIN: When this interview goes to print, it will be horseshoe crab mating season in the Great South Bay and Fire Island. Is there anything you want to discuss with the readers concerning the species and this time of year?Tanacredi: First and foremost if you see them on their backs “just flip them.” If you see horseshoe crabs mating, please just observe with a distant eye and leave them be. If you have the time – and it’s only a few days each summer, consider becoming part of the Molloy horseshoe crab inventory program. Email me at jtanacredi@molloy.edu. This is our program’s 16th year. There are several monitoring groups, but we are the largest and most comprehensive inventory group in New York. Horseshoe crabs have tremendous site fidelity. They go back to the same place to breed if they survive. Only one in 3-million eggs actually becomes a breeding adult. The NY DEC mainly does quantitative studies and uses numbers to issue permits for the collecting of horseshoe crabs to be used as bait. Our studies on the other hand are qualitative. We look at the quality of the beach site. I personally believe it is more important to understand whether an animal is com- ing back to a certain beach. If they’re not coming back there’s reasons we need to understand. Certain beaches have been designated as “breeding beaches,” we are hoping to see more of that.

FIN: In spite of conservation efforts, harvesting of horseshoe crabs in the Great South Bay still continues, and many baymen see it as their rite of heritage. What is your opinion about this? Tanacredi: Well, fishermen have a point of view. Horseshoe crabs have historically been used as bait, but they once were used as a fertilizer as well, and no longer are. Now they “donate” their blood, which is indispensable in the medical industry. They provide a service for all human kind that I believe has higher priority. Commercial fishing has had some tough times on Long Island. There has to be greater emphasis looking at alternative baits, and this directive has to come from the states. The idea of losing an organism for commercial use, and with tremendous pressure and habitat loss along the coastline, after they have survived hundreds-of-millions of years is unthinkable – things needs to be restructured. New York has a restrictive number on harvesting, but not a moratorium. After crabs are bled they need to be returned to our waters so they can go back where they came from. This issue only gets exciting this time of year, but this is a global matter we work with horseshoe crabs all year long. The interesting thing about an organism’s extinction is that it happens overnight. Sheer numbers should not allow us to take for granted that these animals will recover.

FIN: Is waterfront development and bulkheads a threat to the horseshoe crab, and if so what can be done?Tanacredi: Even though the state monitors the numbers of permits it is still not enough to protect them into the future when you count all of the other factors that are impacting them. Some are lost when harvest- ing their blood, they are lost when there is no habitat left, and certainly lost if they are not allowed on breeding beaches because of someone on an ATV or the need to have a bathing beach. It’s really important that these animals are conserved into the future. As a person who studied the associations between storm protection along the coastline and transportation impacts, it’s a story unto itself. I’ve experienced of a Level 5 Hurricane with Camille in 1969, when we talk about the impact of Sandy, the creation of the inlet, the flooding, and dam- age along the coastline – that pales in comparison to what a Level 5 Hurricane could do to Long Island. The main reason I say that is that 85% of the U.S. population live near the coastline. I call it our coastline under siege. We are fairly cavalier in thinking that we’re prepared. We’re build- ing infrastructure now along the coast at a greater rate than even before Sandy hit. The endless iteration of these environmental insults get promoted in the media, called “mega-projects.” Instead of building bigger, may- be we have to build smaller. I believe every level of administration is plagued with not looking at the past, and not learning from mistakes, and things that were misunderstood decades ago in Long Island’s environment.

FIN: I understand you are on board with the concept of declaring Fire Island a world heritage site. Why do you believe this is justified? Tanacredi: Molloy is a Catholic college, founded by Dominican nuns over 60 years ago. Today with the Pope’s Encyclical dealing with protecting the earth, Cardinal Peter Turkson, who was responsible for putting that report together for the Pope, was here at Molloy. I’ve been working for many years with a gentleman, I’m sure you’ve heard his name, Irving Like. As an attorney he is iconic when it comes to environmental issues, he fought Shoreham Nuclear Power Plant and he was one of the originators for the founding of Fire Island National Seashore. Now he, together with Gerhard Stoddard, they have founded Fire Island Conservancy with a mission to establish Fire Island National Seashore, not only as part of the Nation- al Parks Service, but a World Heritage Site. This is so appropriate right now with all the environmental issues going on with New York and Long Island at this time. My transition to Molloy finally helped me have a stable place to keep their message.World Heritage status allows for greater protection, greater emphasis on a place’s natural and cultural amenities, like the Statue of Liberty, Ellis Island, like places around the world that have this designation to protect its global legacy and unique- ness for future generations because of its importance for everyone on earth – cultural places like the Taj Mahal, as well as natural places like the Serengeti. However UNESCO [United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization] has never had a cultural designation for a species. I don’t believe you get a better representative of all species on earth other than the horseshoe crab. So we are trying to push for Fire Island as a World Heritage Site, and the horseshoe crab as a World Heritage Species at the same time. We are in the beginning stages, it’s a big job, but it’s starting to gain interest.