by Christopher Verga

The Gilded Age estates of the Domino Sugar Havemeyer family, Chicle Gum Company’s Thomas Adams, and the Vanderbilts dotted the South Shore. These families flooded the surrounding communities with disposable income for entertainment. The wealth of these families built some of the most famous seasonal resorts on the East Coast, but inland traversing the downtowns was the new theaters that were the heart of community pride. Expanding from New York City’s estimated 48 Vaudeville playhouses, various entertainment was taking root within the South Shore communities. But within less than 30 years, the lucrative opening act of vaudeville along the resort communities will bear witness to its final show of being forgotten.

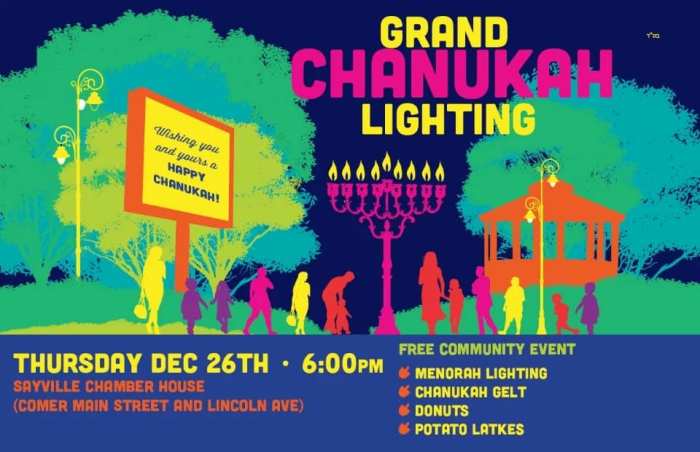

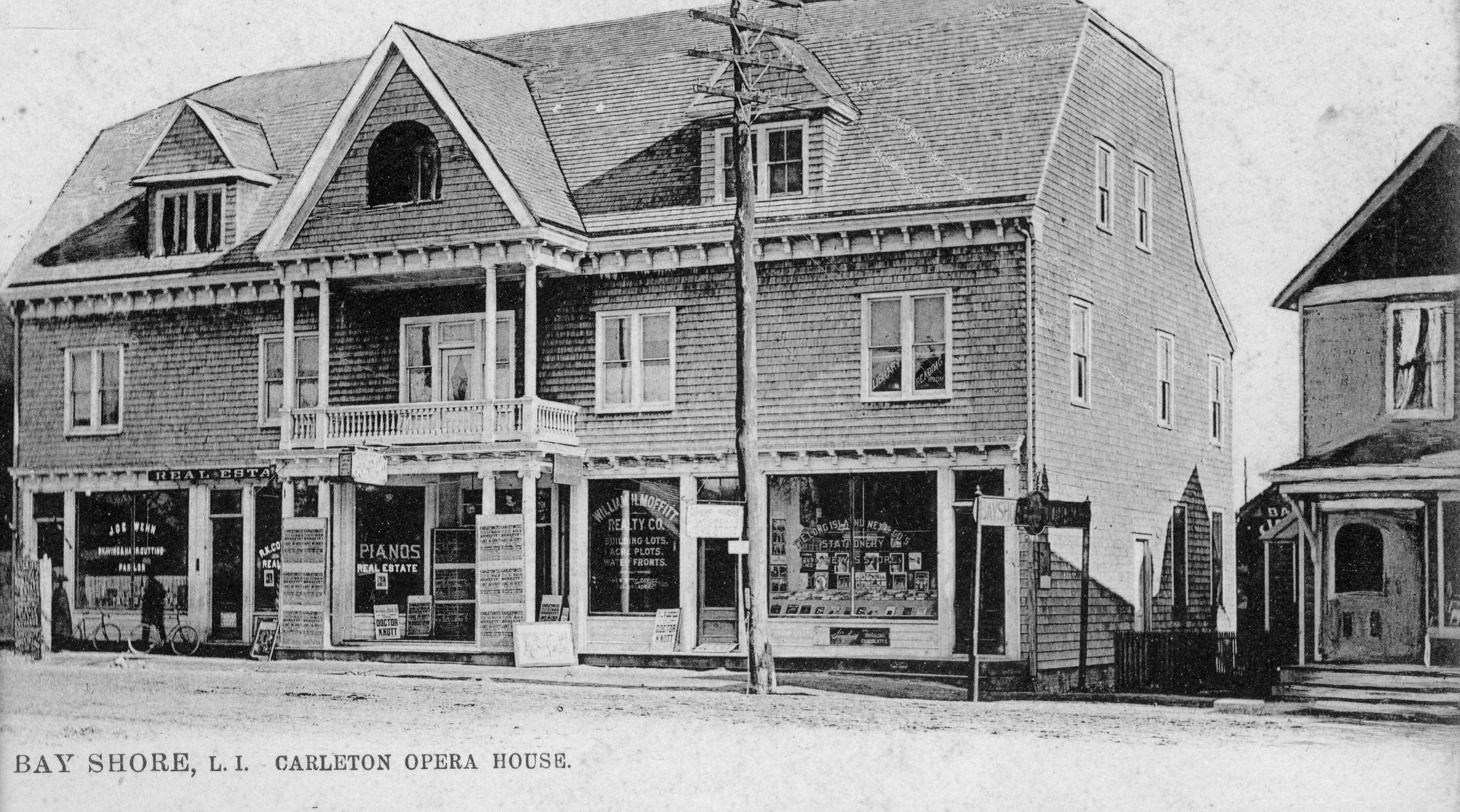

A postcard image of the Bay Shore Carleton Opera House, circa early 1900s.

The Gilded Age resort hotels of Bay Shore and other South Shore towns offered fishing, relaxation, and fine dining, but tourists wanted the selection of New York City theater entertainment.

Building on the demand for stage performances, Carleton Brewster, former Islip Town supervisor and real estate investor, built the Bay Shore Carleton Opera House in the early 1900s.

Once constructed, the opera house contracted residency performers from traveling vaudeville group Proctors, Hyde, and Behrman’s Circuits. Proctors, Hyde, and Behrman shows ran on a consistent timetable advertising in the local newspaper South Side Signal. The plays included “Harvest Days” and “The Stolen Bride,” with headlining city actors like Neil Twomey.

In 1903, due to the growing ticket sales, Carleton Opera House hosted some of the most prominent names in the theater with innovative guest performances by Corse Payton Stock Company. Corse Payton was a familiar name in many New York City middle class circles due to their residencies in the most upscale Brooklyn theaters.

The rejection of traditional performances of classical Shakespearian plays and a strong embrace of popularized slapstick comedy, romance, or dramas made a Payton performance stand out. Payton company’s other distinct feature was the large inventory of movable stage props, which shifted with speed between acts and intermissions.

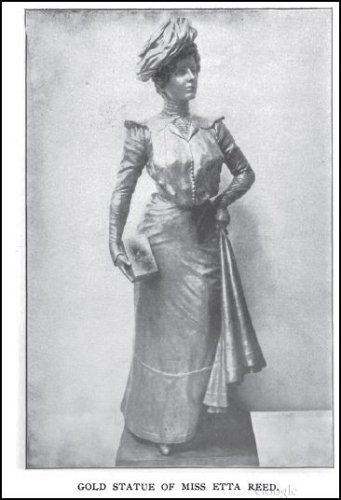

Statue of Etta Reed, wife of Corse Payton.

The August 1903 lineup for Payton’s Company included the plays “A Parisian Princess” and “The Sultan’s Daughter.” Both were romances started by Payton’s wife, Etta. Unlike many traveling theater troupes, Payton company stars will transition into silent movie acting in the decades to come.

The popularized resort communities attracted the Brooklyn-based American Vitagraph Company to film their 1915 blockbuster hit “The Goddess” in Pepperidge Hall estate in Oakdale (the neighboring estate next to Vanderbilt’s Idle Hour) and other South Shore communities.

The following year, Ralph Ince, inspired by the scenic shoreline, opened a studio on Fourth Avenue in Bay Shore. To be closer to the studios. leading actress and actor Anita Stewart and Earl Williams took up residency in Brightwaters. This is going to be the beginning of the end of Vaudeville theater.

The actors that once graced the stage with a strong presence made way for a new generation of celluloid heroes on a movie screen. The Vitagraph Company of Bay Shore produced 26 movies in their first year, which promoted the expansion of movie theaters such as the Bay Shore Regents Theater. The Carleton Opera House scaled back on its lineup of plays for motion pictures and financial planning offices.

Surrounding communities soon abandoned live performances for movies, creating a new generation of heroes who quickly forgot about traveling vaudeville acts. By 1927, the Carleton Opera House was torn down to make way for a new commercial development.

Percy Williams, a vaudeville actor who bought multiple theaters, including the Brooklyn Music Hall, Orpheum in Brooklyn, and the Bronx Opera House, built his 48-acre country estate Pine Acres in East Islip. By the early 1920s, Williams sold his theater holdings and amassed a fortune of $5 to $6 million, estimated at $87 million today.

While summering along the South Shore, he witnessed first-hand the challenges aging stage actors faced with the motion picture revolution. At age 66, Williams died, leaving $5 million and his 48-acre estate to aging indigent actors. Before his death, Williams wrote in his last will and testament, “I made my money from the actors; I herewith return it to them.” Within William’s Old Actors Home, former stars of the stage had their last act in their sunset years of life.