“They do not want to learn English, they are taken away the jobs of real Americans, their religious doctrine teaches disloyalty to traditional American values, and they are the cause of a higher crime wave.”

The above statements were the Ku Klux Klan’s argument for an anti-immigration platform, highlighted in their monthly magazine, “The Kourier,” or the newspaper “Vigilance,” which circulated among the one in seven Long Islanders that had an allegiance to the Klan.

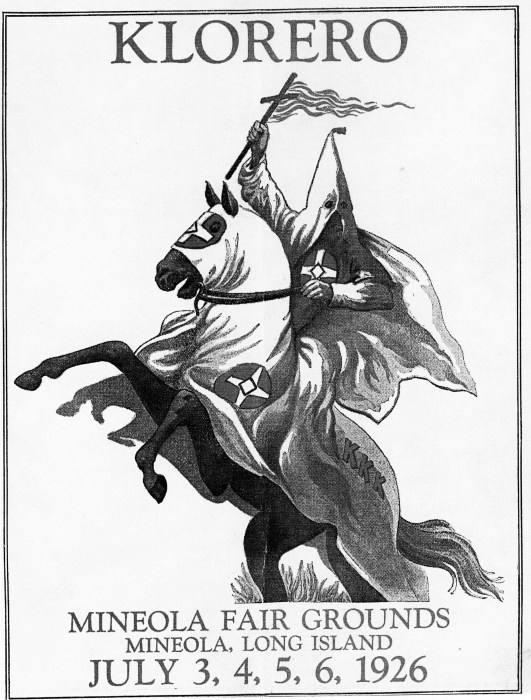

Groups that were the target of the local Klan were Catholics, Italians, Jewish people, and people of color. Rallies numbering in the tens of thousands from the Mineola Fairground to East Islip’s Heckscher State Park left the crimson aurora of burning crosses for locals to fear.

Despite all the indifference in the world, symbols of empowerment can be found in something as simple as an unnoticed wild flower growing in a dense forest. This would be the rebuttal St. Therese Martin would bestow to her desperate followers, who referred to her as Little Flower.

Father Bernard Quinn, a Chaplain on the Western Front during World War I, struggled to find any sense of divinity in fields of death and destruction. Quinn would discover Little Flowers’s philosophy to find solace in God’s divinity, which can go unnoticed but still be present even in the trenches of brutal warfare. After the war, Quinn used this inspiration to build his parish within the underserved Black community of Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn.

As he became a successful advocate for quality-of-life issues in his adopted community, the Great Depression took root. Due to limited services, increasing poverty, and intuitional racism, orphaned children of color became the most underserved group. Turning to his congregation for monetary support, Father Quinn laid out his vision for an orphanage in the scenic town of Wading River, Suffolk County. The name of this orphanage would be Little Flower, named after Saint Therese Martin, whom Quinn’s congregation prayed to for protection. Unbeknownst to Quinn was that raising the funds to purchase the land would be the easiest part.

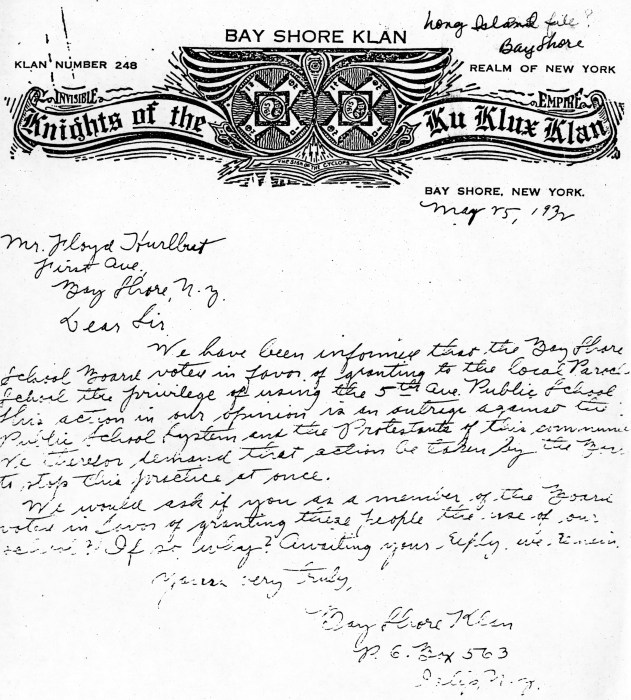

In 1931, the same year Quinn opened his orphanage, the Klan was near its peak membership on Long Island. Within 10 years, Bay Shore saw a significant jump in the immigrant population, which was mainly Catholic. St. Patrick’s Church became a sanctuary for newcomers and a target for the local Klan.

Utilizing rumors that St. Patrick’s Knights of Columbus was a secret militia destined to overthrow the Protestant establishment of Suffolk County, all Klan-endorsed candidates secured positions within Islip town offices.

In opposition to the Klan influence, Father Donovan mobilized the Holy Name Society for a rally numbering as many as 40,000 people. The extensive support at the time did little to break the Klan stranglehold on politics but reflected the growing shift in power.

Twenty- Six miles east of Bay Shore, the Riverhead town chapter of the Klan narrowed their focus to the Little Flower Orphanage. Little Flower represented everything the Klan despised: people of color, Catholicism, and immigrant labor, which tended to the daily operations of the orphanage.

After countless threats from the Klan, Quinn put his faith in God and the philosophy of becoming the Flower of a divine light in a dark forest. Within a year of being opened, the Klan would torch the orphanage. After the orphanage was burnt down, Quinn rebuilt it bigger and better. Soon after being rebuilt, the Klan would burn the orphanage down a second time. In response, Quinn would build it back bigger and stronger, understanding that his symbolism of divine love would withstand the Klan’s hate.

Today, Little Flower services a little under 1000 children, young adults, and adults, providing a range of services, which include foster care, mental health treatment, day programs for adults with developmental disabilities, and special education services.

The small handful of workers Quinn employed has grown to 500 people today. But one of Quinn’s biggest achievements was pushing the Klan into the trash heap of history by becoming a symbol of love that withstands the test of time.

Father Bernard Quinn is presently a candidate for sainthood.