It was 1986, and Babylon Town faced an insurance liability crisis. After days of analyzing and crunching the numbers with economic experts, town supervisor Anthony Noto announced that the only reasonable cure would be an all-out ban on surfing Cedar and Gilgo Beaches.

Babylon’s liability insurance premiums tripled to $180,000. Building on the higher premiums, coverage was reduced from $25 million with a $100,000 deductible to $5 million with a $1 million deductible. In an attempt to negotiate a last-minute deal, the town allowed the insurance policy to expire, leaving the town without insurance. Statistically, out of 1000 surfers, 6.6 will face some bodily harm, which would leave the town liable for a lawsuit while having no coverage. The Babylon beach of Gilgo and the surrounding South Shore beaches attract an estimated 8000 surfers. Fanning the flames of Noto’s concern was the recent drowning of a surfer in Gilgo. Defending his position, Noto stated, “I can’t play Russian roulette with the taxpayers’ money.”

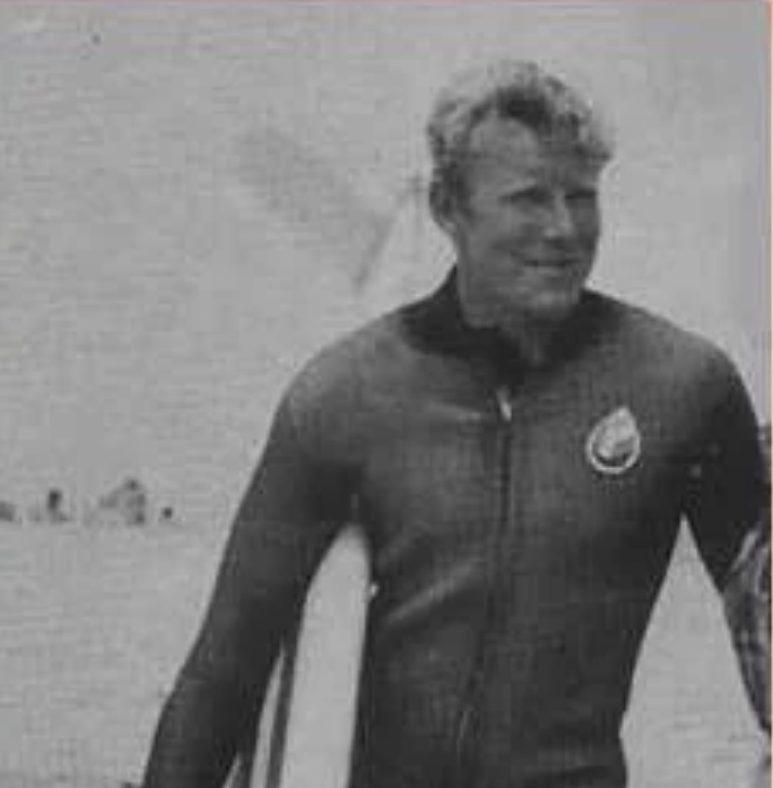

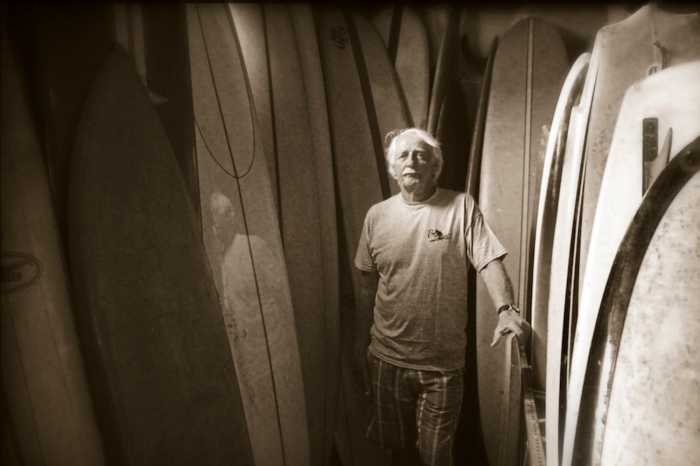

Reaction among the surfing community was swift. All town meetings were packed with hundreds of surfers referring to Noto as “The Supervisor Who Stole Summer.” The swift mobilization was due to Gilgo Beach’s significance to the community. Gilgo was a perfect spot for wave breaks and ground zero for Long Island’s surfing culture. Gilgo hosted one of the first surfing Eastern Championships, which united West and East Coast talent. It was the everyday collaboration of skills that harnessed world-surfing championship contender Eric Eastman of Bay Shore. Gilgo would be where Rick “The Raz” Rasmussen, who would dominate the US Surfing Championships from 1972 to 1974, trained. Gilgo wave breaks inspired Charlie Bunger to design his nationally renowned surfboard, the Bunger 360. Most of all, Gilgo unified multiple generations of surfers, from the Baby Boomer to the Gen Xer.

During a series of town meetings related to the ban, Eric Eastman addressed the board, stating that “the surfing ban amounts to an assault on the basic freedom of Americans to act of their own free will. I have a surfing friend who was wounded while defending our country at Tarawa during World War II. Can anybody now deny him the right to surf in his own country and at his own risk? We should rid ourselves of this oligarchy of insurance men and their minions of lawyers. They want to institutionalize our world sports and make us a nation of spectators instead of seeking the pure exhilaration of riding a wave.”

After the town meeting, in a statement to the press, local lawyer and Eastern Surfing Association member Michael Angiulo said, “The town of Babylon is creating an issue where there is none. Everyone realizes the chances of a surfer suing a town successfully are nonexistent.”

In closing, Angiulo assured the Eastern Surfing Association would file a suit against any ban enacted. In response to the pushback, Town Board member Lou Maestri stated, “This ban created a hornet’s nest. The town should keep its current policy allowing surfers to use the beach at their own risk.”

By June, surfers and the town started to frame a compromise. The Eastern Surfing Association will promote a new safety policy for local surfers, and in turn, the town will drop the proposed ban. But Eric Eastman had a nonnegotiable demand before the surfers drew in their claws. From his personal surfboard collection, he wanted to donate a board used by legendary surfer and advocate Duke Kahanamoku to the town, which he wanted to hang in the board meeting room above the map of Long Island. This symbolic act will always remind the town of the surfer’s role in the community. In a gesture of goodwill, Noto agreed and had the board put it in a glass case. In a press statement, Noto stated: “They’re winning by saving surfing, and we’re winning by getting the safety features that we could never get before.”