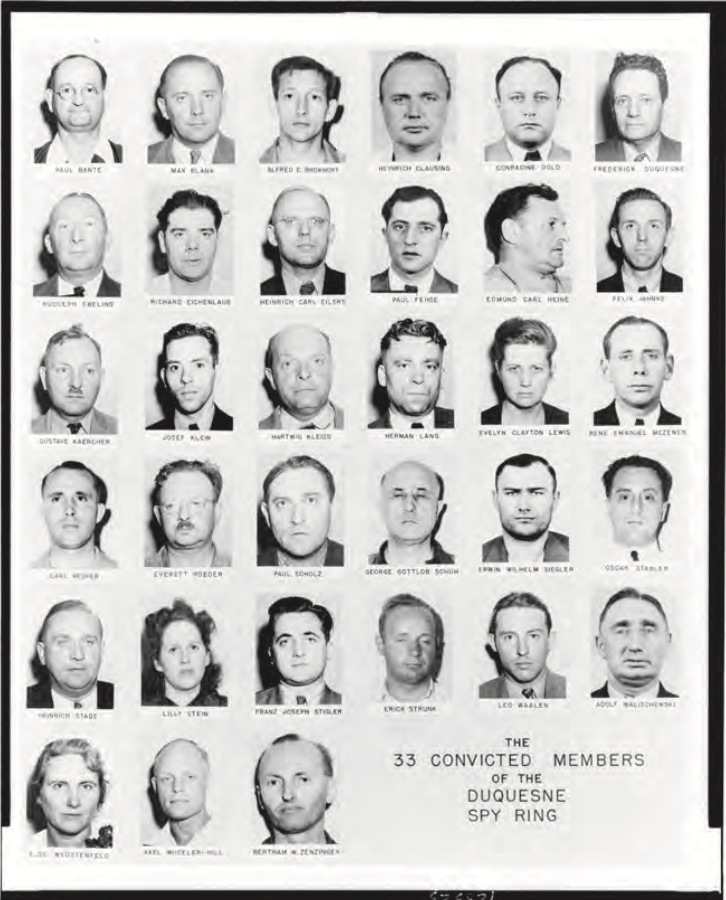

Mug shots of Duquense Spy Ring members after it was broken up by the FBI.

The term Arsenal for Democracy is reserved for cities such as Detroit, leaving Long Island out of the historical corridors of World War II’s wartime manufacturing. In contrast to novice historians, Long Island was home to one of the most advanced wartime aviation industries. Manufacturing hubs Grumman, Fairchild, Ranger, Liberty, Sperry, and Republic Aviation are some companies that made Long Island their base for operations. The largest of these defense contractors include Sperry, Grumman, and Republic, each of which had work forces numbering in the thousands.

Setting national industry records, Grumman produced 12,275 Hellcat fighter planes (450 a month) and 9,835 Avenger bombers (2,000 produced in the Grumman Bethpage facility). Shattering Grumman’s record was Republic Aviation’s production of the legendary fighter plane, the P-47 Thunderbolt. In total, 15,579 Thunderbolts were built, equipped with all the cutting-edge technology of the time, to achieve the ultimate goal of defeating Hitler. All the production milestones, innovations, and skilled labor forces became an incentive for industry spies to embed themselves into the greater fabric of the Long Island community.

On a Saturday morning, June 28, 1941, the small community of Merrick was overrun with FBI agents and local law enforcement descending on 210 Smith St. Homeowner Everett Roeder was escorted from his house in handcuffs. On looking, neighbors described Roeder as very quiet, rarely speaking to anyone outside of brief pleasantries. Roeder, a mechanical engineer at Sperry Gyroscope Company, worked on projects that included bomb sights for planes. After a lengthy investigation following FBI agents intercepting a Nazi radio transmission coming from Centerport, a network of more than 30 Nazi spies was discovered weaved into the fabric of the New York metropolitan area. Many members of the ring had a membership or connections to the pro-Nazi German American Bund, which had one of its headquarters in Yaphank. The spy network, referred to as the Duquesne Ring, was organized by Fritz Duquesne, a German Bund member and trained Nazi spy who worked directly with the Gestapo. Roeder, an active participant in Duquesne, had the code name Carr. The conspirators would transmit 300 messages and receive 200 messages from Long Island to Hamburg, Germany, via shortwave radio. American Double Agent William Sebold provided statements to the FBI that he was given $22,000 within two years from Nazi Germany to pay the active members in the network.

As one of the dozens of people, Roeder received multiple payments of $300. Roeder worked directly with Japanese Agent Lieutenant Commander Takeo Ezima, who served Japanese and Nazi German interests. Roeder provided detailed plans for the wiring system for fighter planes in return for the payments. The other spies within the network had employment in New York City shipyards, Ford Motor Company, Chrysler Motor Company, New York-based American Gas and Electric Company, and Westinghouse Electric Company. The FBI dismantled the Duquesne Ring swiftly with minor damage in intelligence leaks to the Nazis. The rapid response was due to another local spy ring that went unnoticed two years prior.

In 1938 a spy ring was organized across Long Island and New York City to gather as much intelligence for the Nazi cause through industries such as Republic Aviation. The head of this ring was Karl Schlueter, an agent in the Nazi intelligence service. Active members of the ring included Otto Voss of Floral Park, who worked at Republic Aircraft Company in Farmingdale; Erich Glaser, an enlisted private stationed at Mitchel Field, Hempstead; Gustave Rumrich, an AWOL army soldier; and Johanna Hofmann, who worked on German ocean liners that were coming in and out of New York City ports. Following the breakup of the 1938 spy ring, the FBI discovered a Nazi short wave radio station and spy safe house nestled in the dense pine forest of Wading River, referred to as the Benson House. This was an ideal location for a short-wave transmission station due to many pine trees around the house hiding the antennae and generators.

Discovered through agents’ investigation of the property was a connection to Nazi-aligned companies in New York City that directly participated in the Nazi cause or daily operations of the spy rings. One regular contact in the network of Nazi spies was Elmer Carlton, owner of Remle-Carlton Shipping Company of Manhattan. His company was under suspicion of Nazi activities due to the Yaphank German Bund using it to receive goods from Nazi Germany. New York City-based Remy and Company, which advertised itself as a chemical shipping company, was a front for various intercepting Nazi spy networks. But the most important intelligence gathered was how the Nazi spy ring operated and what intelligence they were targeting. The breakup of the 1938 ring and the discovery of the Benson House created a foundation to successfully weed out spy networks such as Duquesne Ring with limited intelligence leaks.

Following the successful breakup of the large-scale spy rings, Long Island would see an unsuccessful wave of smaller-scale networks through the duration of America’s involvement in the war. An example of this was Frank Hart of Arizona Avenue in North Babylon. Years before America’s involvement, Frank would become active in the Nazi party in Germany and hold the rank of Reinsfueheer’s Storm Trooper. Upon his return to Babylon, he enlisted in the Army Air Corps. While in the Air Corps, Hart provided information on military plane weaponry to Nazi agents.

Republic Aviation’s rusted, last remaining hangers in Farmingdale are commonly a testament to American ingenuity. The internal and external intelligence threats of “loose lips sink ships” were conveniently left out of local history due to the dominating narrative of a community coming together for a cause more significant than themselves.